Everybody has a right to judge James Horner's music and not to like it.

Generally this disenchantment is reflected in terribly pejorative verbs such as dig up, borrow, pump, copy, plagiarize … The kind of actions the composer is accused of, putting forward the idea of a lazy craftsman's poor and sloppy work: the pickaxe as an unsubtle tool, borrowing as a sign of weakness, pumping for large quantities, copying for the lack of creativity, plagiarism as a lack of respect towards the other composers.

It is difficult to go against this phenomenon because the allegations are undeniable:

Indeed, it is indisputable that James Horner replicates ideas from his earlier music to transpose them in his new compositions (intrinsic similarities of his work), and there is no question that many of his ideas are inspired by previous works by other composers (extrinsic similarities of his work).

Indeed, it is indisputable that James Horner replicates ideas from his earlier music to transpose them in his new compositions (intrinsic similarities of his work), and there is no question that many of his ideas are inspired by previous works by other composers (extrinsic similarities of his work).

"(…) when we judge as we feel it is always wrong in something, though never wrong in anything, when judging as we conceive. "Malebranche, The Search After Truth: With Elucidations of The Search For Truth

[divider]Why is it so difficult to appreciate his music? [/divider]

In One must learn to love, one of the short aphorisms of his book The Gay Science (1882), philosopher Nietzsche explains that learning to love a musical work requires some effort.  He therefore describes three phases:

He therefore describes three phases:

He therefore describes three phases:

He therefore describes three phases:

First, we must learn to identify, to discern and discover the themes, the melodies, the structure, and the different moments of the work.

Then comes the phase of the effort when the work must be "understood" for what it is. Despite its strangeness one must "be patient with its appearance and expression, and kindhearted about its oddity."

Only then the final phase will come: fascination, "until we have become its humble and enraptured lovers who desire nothing better from the world than it and only it."

What we learn from this discourse is essentially the notion of effort. In order to truly appreciate the music, one would have to go through a long process, especially with the second phase, which would consist, according to Nietzsche, of accepting the singularity of the work.

But we may think that with James Horner, redundant ideas would tend to reduce this singularity and thereby would facilitate its acceptance … Yet it is not the case. Everything seems to take place in this first phase of the discovery.

The main problem is this: for an experienced listener, intrinsic or extrinsic similarities seem to be unacceptable from the very first listening. He cannot therefore fall in love with this music, because the first contact is negative, thus preventing him from going further, and being properly invested in other listenings.

[divider]How is such an opinion formed?[/divider]

Beyond objectively bringing to light the facts (intrinsic and extrinsic similarities), the judgment of values, which everyone has, does mainly represent the first opinion.

Take for example the four-note motif, which is so dear to the composer. To notice its regular appearance in his works is a judgment of fact, related to the object, i.e. the score being listened to. While assessing this regularity is, however, proper to each subject, and therefore becomes subjective.

Thus, among listeners, the subjective acceptance of the similarities plays an important role in the development of the first opinion.

Let us take a look at Kant who particularly distinguished three types of judgments, in Critique of judgment (1790) : the Beautiful, the Pleasant and the Good.

If the subject claims to dislike this reprise of the four-note motif, or intrinsic and extrinsic similarities, this is neither, as Kant defined it, an "Aesthetical Judgment" (1) (disinterested and free satisfaction, indifferent to the existence of the object), or a "Sensory Judgment" (2) (which makes me happy, which is nice for me because it sparked a desire inside me) but rather a "Cognitive Judgment" (3). as we will see.

Indeed the case of “Aesthetical Judgment” or “Judgment of Taste” (1) would be appropriate for a person who is not familiar with James Horner's work, and who is not necessarily sensitive to film music or even orchestral music. The similarities or the four-note motif have no meaning for them. (the satisfaction is indifferent to the existence of the object). Thus, his judgment would be expressed like this: "I find this music beautiful" or perhaps inversely "this is not the style of music I listen to."

"Sensory Judgment" (2) could correspond to a certain part of the audience because it involves the sensitive nature of the latter, assuming or producing a need, creating a need. Thus, as an admirer of the composer, a "Sensual Judgment" could be expressed like this: "I am pleased to listent to Horner's latest work" because listening to music follows a long wait filled with hope and questioning. It is a pleasure directly related to the existence of the object, which has an arbitrary and dependent aspect of strictly individual concept of fun. In fact, it is part of a personal mode of appropriation and consumption.

We are far from generalizing, but we believe that the majority of music lovers or "soundtrack fans" has a reasoned opinion on each new piece of music they listen to (and we belong to such group of people), and rather expresses a judgment called "Cognitive Judgment" (3). That is to say that the opinion is focused on the good and involves the notion of concept. It is therefore a matter of demonstrative reason.

Thus, we believe that most connoisseurs who dislike James Horner's music do not approve, in whole or in part, intrinsic and extrinsic similarities. Because these do not meet their conception of music, these repetitions are against the values they are trying to share and be recognized by others.

Thus, we believe that most connoisseurs who dislike James Horner's music do not approve, in whole or in part, intrinsic and extrinsic similarities. Because these do not meet their conception of music, these repetitions are against the values they are trying to share and be recognized by others.

[divider]The sensitive and the understanding. [/divider]

Following this observation, let us therefore turn to this "Cognitive Judgment". While the "Aesthetical Judgment" results solely from sensitivity, Kant separates two faculties which are involved together and form the structural component of a "Cognitive Judgment": sensitivity and understanding.

Sensitivity helps us receive sensations, what happens to us when objects (music) are given to us, while understanding is our ability to comprehend the objects, to think through them. It organizes our knowledge.

Kant in his Critique of Pure Reason endeavors to show what happens to the sensitivity (receiving sensations), which comes down to the understanding (knowledge building), how these two faculties operate, and illusions in which we fall if we rely on one of the two only.

This "Cognitive Judgment" (I like or I do not like this nth reprise of the four-note motif, because …) is not entirely subjective, because even if it is issued by the subject (subjective aspect) it is supposed to be built around concepts in order to make others understand. It thus targets objectivity. When we speak of a "Cognitive Judgment", it therefore involves the effort of a subjectivity that wants to share its knowledge with other subjectivities.

This is the challenge of this article: from recognized extrinsic similarities to use reason, beyond the sensitive and "Judgment of Taste", in order to share our judgment on them.

We love James Horner's music because our "Cognitive Judgment" leads us to think that the similarities are based on viable concepts. Thus, confronted to sone similarity, our judgment is as follows:

First, our sensitivity allows us to receive a similarity positively. For us it is not strange. Nietzsche moreover insisted on the notion of strangeness. He said we had to show good will, and avoid being in a position of resilience and closure. Thus, strangeness "gradually sheds its veil and turns out to be a new and indescribable beauty."

Then our understanding or intellect, leads us to believe that this similarity exists for a valid reason. Thus we are led to try and understand it according to our conception of music. For us, all the similarities and quotes have meanings and therefore legitimacies.

In this way of thinking was born our willingness to nuance two ideas conveyed by the web about the composer.

[divider]Two dissected untruths[/divider]

According to the dictionary of the French language Le Littré, untruths are "words expressing a sense being contrary to that we want to be heard."

These words are sentences we have identified on the Internet which claim that James Horner is inspired lazily or without valid reasons by recent compositions:

A – The theme of Troy (2004) is copied from David Arnold's Stargate (1994).

B – The theme of Enemy At The Gates (2001) is copied from John Williams' Schindler's List (1993).

In the Dictionary of Pedagogy by Ferdinand Buisson (1887), Ludovic Carrau explained that there are cases where the judgment is so obvious that "it is made itself;, the reflection may not be absent, but it is limited to exactly design the terms and put them in front of each other; their suitability or unsuitability immediately appear."

Here we would like to suggest that the associations Troy/-Stargate and Enemy At The Gates/-Schindler's List are based on a judgment that was made too quickly. The combination was so obvious to some people that a prolonged reflection was not necessary. It could have been though. Here' is why.

[divider]A – First untruth: In Troy James Horner used the theme of Stargate. [/divider]

The concerned theme appears for the first time in Troy when Achilles and Briseis talk:

Briseis: Soldiers understand nothing but war. Peace confuses them.

Achilles: And you hate these soldiers.

Briseis: I pity them.

Achilles: Trojan soldiers died protecting you. Perhaps they deserve more than your pity

Briseis: Why did you choose this life?

Achilles: What life?

Briseis: To be a great warrior.

Achilles: I chose nothing. I was born and this is what I am.

Even if this theme will then be associated with the romance between these two characters, the underlying discourse is that of war and its usefulness.

Then the theme in the final Through the Fires, Achilles … and Immortality fully flourishes on the images of the Trojan city in flames.

The film closes with Ulysses' words and leaves room to questioning: how could such a war, killing thousands of people among the two peoples, be started because of a woman …?

What is the link with Stargate then?

Do not look for it, there is no relation except maybe the structure of the themes (combinations of four notes) or the color of the sand beaches along the Aegean Sea that looks like the desert of the planet Abydos, visited thanks to the stargate in Roland Emmerich's movie.

On the contrary the link with the theme heard sixteen years earlier in Burning the Town of Darien (Glory-1989) is obvious. This track appears in the film when the 54th regiment participates against its will in the ransack of a village. It is destroyed by fire and the black soldiers are questioning the meaning of their actions and the legitimacy of the order that was given to them.

It is not surprising then to find in these two films the same musical idea to represent houses ravaged by fire, as well as the same questions about the meaning and utility of a conflict. This is an intrinsic similarity of his work which is meaningful.

Thematically and harmonically, each transition or evolution, is part of a very special building of which reflected or spiritual content forge architecture.James Horner

Because their sensitivity prevents them from recieving this similarity, because their understanding leads them to hastily conclude that James Horner has lazily been inspired by David Arnold's theme, some formulate a negative "Cognitive Judgment" on the theme of Troy.

As for us, our understanding pushes us to continue our reflection.

Where does this theme in Burning the Town of Darien come, which inspired James Horner years later in Troy?

Where does this theme in Burning the Town of Darien come, which inspired James Horner years later in Troy?

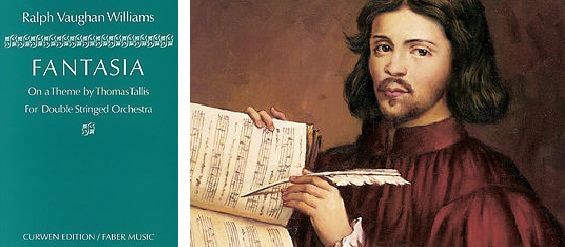

This fifteen-minute piece was named after the original composer of the melody, Thomas Tallis (1505-1585), who inspired Ralph Vaughan Williams almost 400 years later.

The most important is that this theme from the Renaissance (1567) is accompanied by a text inspired by an Old English psalm evoking … the meaning and usefulness of the war!

Why fum'th in fight the Gentiles spite, in fury raging stout?Why tak'th in hand the people fond, vain things to bring about?The Kings arise, the Lords devise, in counsels met thereto,against the Lord with false accord, against His Christ they go.

Multiple versions / translations exist:

Why do the heathen rage, and the people imagine a vain thing?The kings of the earth set themselves, and the rulers take counsel together, against the LORD, and against his anointed, [saying],Why do the nations rage, And the people plot a vain thing?The kings of the earth set themselves, And the rulers take counsel together,Against the LORD and against His Anointed, saying,Why are the nations so angry? Why do they waste their time with futile plans?

The kings of the earth prepare for battle; the rulers plot togetherAgainst the LORD and against his anointed one.Why do the nations conspire and the peoples plot in vain?The kings of the earth take their stand and the rulers gather togetherAgainst the LORD and against his Anointed One.source : blueletterbible.org

Considering this, it is difficult to think of Stargate as an inspiration for the theme of Troy because this is ultimately the extension of a theme which was written half a millennium earlier with the same meaning.

The way I practice comes from the repertoire; it is 500 years old and I don't mind if it does not move with the times. (…) And one of my claims is to remain faithful while perpetuating my speech. 1James Horner

You can listen to Ralph Vaughan Williams' full piece and to a sample of Thomas Tallis' theme by following this link: Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

[divider]B – Second untruth: In Enemy At The Gates James Horner used the theme of Schindler’s List by John Williams.[/divider]

Just like the theme of Troy, discussed above, the theme of Enemy At The Gates was born from a transition in the composer's work. First, it was heard for the first time in 1995, two years after Schindler's List, in the snowy plains of Alaska, where the action takes place in the animated film Balto.

Indeed, this theme will appear for the first time through a horn solo in a cue that is not on the album, when the main character Balto, a husky dog, annoyed and leaving the city, sees wolves at a distance. This vision seems to awaken a strength, a hope which were asleep inside him. Later in the movie we find the theme a second time during the cue Heritage of The Wolf (1'28): Balto, carrying serum to save the children of his village from diphtheria, is caught in a snowstorm and finally, completely exhausted, is losing hope. Suddenly a majestic white wolf goes to him and gives him a new impetus, and strength to continue his journey.

Then it migrated the same year in Apollo 13 in the cue Re-Entry and Splashdown (2'52). When the contol module Odyssey returns to the atmosphere, the radio signal stops for a few minutes. Trumpets sing this theme during this prolonged critical moment, when relatives and NASA technicians begin to despair due to the absence of any sign of life from the astronauts.

Two years later in Titanic (1997), during the song Death of Titanic (6'16) the theme is played in a very short version by the strings. It is at the end of the sinking, when the stern floats like a cork in the dark in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean and the situation seems hopeless.

Finally, in The Perfect Storm (2000) the theme accompanies desperate faces of the members of the helicopter crew when they realize that they are unable to refuel and are in perdition.

The common element between these four situations is the breaking point between hope and despair. Each characteris faced with stressful events that are morally and / or physically hard to live through.

The battle of Stalingrad, filmed by Jean-Jacques Annaud in 2001 is characterized by the harshness of its urban fights, which also affected civilians. These six months of confrontation and thousands of daily deaths have had a psychological impact on men and women who were there. It is then not surprising to find this theme again at a level of maturation allowing it to hold a major place in the film's score.

Jean-Christophe Arlon described it as "(…) haunting lyricism and feverish "hornerien" derivation which expresses the combination of pain and perseverance, the sacrifice of its aspirations in front of adversity, dignity simply. (…) This sub-theme becomes the vital center, the spirit of the score. (…) These eight-note groups extend and respond successively without strictly sticking to the action but, staying true to the hopes and disappointments of the Vassili / Tania / Danilov trio. " 2

The "Cognitive Judgment" expressing the copying on Schindler's List does not take into account the transition through the three songs that preceded Enemy At The Gates. But it shows that James Horner has gradually made his this theme and that each of its uses is not accidental. All the more since in 1992, a year before Schindler's List, the first eight notes of the theme were already used in Playtronics Break-in (2'12) from Sneakers, the nourishing score by excellence.

Depending on the listener's sensitivity and understanding, following the acceptance and knowledge of the intrinsic similarities in James Horner's work, the resemblance with John Williams' score may therefore be more or less resonant.

For us, from the first listening of Enemy At The Gates, the link with the finale of Apollo 13 jumped to our ears. The only thing that was left to do was to discover the origin of this quote that would then remove the last doubts about the non-influence of John Williams' theme.

Jean-Christophe Arlon put us on the track of Mahler and his eighth symphony. In the Infirma nostri corporis part of this symphony called "des Mille", we can hear the notes that James Horner explored in Sneakers, Balto, Apollo 13, Titanic, and The Perfect Storm.

You can easily hear the theme at the beginning of this version by following this link: Pierre Boulez Mahler Symphony No.8

The lyrics used by Gustav Mahler is as follows:

Infirma nostri corporis,virtute firmans perpeti.Lumen Accende sensibus,infunde amorem cordibus.

These are the words that echo the notes inspired by Gustav Mahler which are contained in James Horner's scores. This is a genuine prayer made in a moment of weakness to find the necessary resources to continue the struggle for life. These words make sense in the drama of the scenes which were chosen by the composer to bring this theme. We believe this is not due to chance or laziness from the composer.

[divider]To conclude…[/divider]

This text was written in response to writings that we think deserved to be clarified. In no way shall we pretend to judge them. We have simply developed our reflection here following our sensitivity and our understanding, to share it and to avoid only one truth to be visible.

Everyone has the right to judge James Horner's music and to not love it. But as a "Cognitive Judgment", it should not be built from sensitivity only but also with further reflection on James Horner's approaches. Their acceptance depends the love of music and the understanding of it.

This is what we have endeavored to show.

As Nietzsche pointed it out, any object in the world is for us, by nature, strange., we must strive to keep an open mind. This openness is essential to have the chance to enjoy a musical work. Providing a warm welcome to each new score, it may well bring us all the riches it contains. "That is its thanks for our hospitality." (Nietzsche)

Photo credits:

Troy: © Warner Bros

Glory: © Tristar

Balto / Apollo 13: © Universal Pictures

Titanic: © 20th Century Fox

Bibliography:

1 J.H. et des poussières : La guerre de Troie aura bien lieu. By Jean-Christophe Arlon and Didier Leprêtre, Dreams Magazine.

2 Il était une fois dans l'Est by Jean-Christophe Arlon, Dreams Magazine.

Websites references:

To me it is less an issue of inherently disliking Horner’s musical quotations on principle, and more that they distract me when attempting to immerse myself in any unfamiliar work of his. For instance, I recently listened to Bobby Jones: Stroke of Genius for the first time and, during the finale, Horner quotes large chunks from his iconic Braveheart theme. It had been a long time since I’d listened to Braveheart, so my immediate reaction was to keep jumping back in the cue, trying to remember where I’d originally heard that theme. This of course utterly interrupted the flow of the experience and undermined my enjoyment of the score. Once the iconic theme was recognized (with some help), that is when cognitive judgement kicked in: we all have strong emotional associations with themes. You wouldn’t just needle drop, say, Williams’ Superman theme in an unrelated movie because a certain percentage of your audience will immediately think of Superman. Granted, Braveheart isn’t quite that famous, but it’s still an extremely iconic piece of music for many. So why deliberately invoke Braveheart in your golf movie? Laziness is the easiest explanation and thus the first that comes to mind, and I find it personally hard to break myself from that impression and continue to enjoy a work. One thinks: here’s a composer who is unable or unwilling to come up with a new way to invoke the same emotion. A composer who is unconcerned by the fact that a feeling of déjà vu will override the intended effect in any audience member who pays attention to the music.

The Real Person!

The Real Person!

Thank you for your message @jens

Regarding Braveheart and Bobby Jones, this is a request made by the director Rowdy Herrington. The temp track was Field of Dreams and Braveheart.