When in 2011 James Horner was offered the Mexican-made Cristiada (re-titled For Greater Glory for its international release), he realized he was placing himself in the service of the faith crowd. And faith-based movies are invariably a risky proposition.

The project marked the directorial debut of Dean Wright, who had acted as special effects supervisor on the first two Narnia movies and had made significant contributions to Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. While For Greater Glory features some commendable digital matte paintings, the production’s modest budget precluded the kind of epic battle scenes that filled the Cinemascope frames of the aforementioned fantasy mammoths. Similarly, Michael Love’s generally well-written script led Wright to focus more on character than on action.

The story deals with the Cristeros war that raged in Mexico between 1927 and 1929, when the country was still reeling from the great revolution and especially the civil war (1914-1915) that had taken a considerable toll just a decade and a half earlier. To compensate for losses sustained by citizens and companies of the United States of America, the 1923 Bucareli treaty allowed the US to exploit a considerable amount of Mexican oil fields. In 1926, the newly elected atheist president Plutarco Elias Calles decided to repeal the Bucareli treaty and curtail the power of the Mexican clergy. While Catholicism is now widely regarded as a staple of Mexican society, the fate of Catholics was significantly more precarious less than a century ago. Resistance to the anticlerical laws took two forms: some protested them peacefully, others took up arms and tried to obtain religious freedom by becoming Cristeros, essentially soldiers of Christ.

While For Greater Glory has the intellectual honesty to at least acknowledge the peaceful resistance, it spends far more time on the other side of the fence, glorifying the violent Cristero uprising. When the dust has settled, the movie asks us to sympathize with religious fanatics, and that probably proved to be the project’s Achilles’ heel. While it did decent business in Mexico itself, the movie struggled to find an international audience and failed to recoup its budget.

Apart from its debatably pro-religious position, and for those viewers either buying into it or willing to look past the issue, For Greater Glory actually holds its ground. Running an ambitious 145 minutes, the movie carries very little excess fat. Michael  Love’s screenplay spends the better part of an hour bringing together an interesting variety of characters and then has them interacting with each other in dramatically satisfying ways. And you have to hand it to the faith crowd: they get their musical priorities straight. In 2011 and 2017, producer Pablo Jose Barroso allotted sizable chunks of very modest budgets to the music department, allowing composer Mark McKenzie (himself a staunch Catholic) to write superlative large orchestral scores for El Gran Milagro and Max and Me, respectively. Similarly, the producers of For Greater Glory wanted a score very much in the Romantic tradition and actively sought out James Horner, who at that point in his career probably jumped at the opportunity to write an unabashedly large orchestral and choral score ripe with unbridled emotionality. It is a sign of these times that it took an obscure and little-seen movie about religious fanaticism for James Horner and the Golden Age tradition to shine once more.

Love’s screenplay spends the better part of an hour bringing together an interesting variety of characters and then has them interacting with each other in dramatically satisfying ways. And you have to hand it to the faith crowd: they get their musical priorities straight. In 2011 and 2017, producer Pablo Jose Barroso allotted sizable chunks of very modest budgets to the music department, allowing composer Mark McKenzie (himself a staunch Catholic) to write superlative large orchestral scores for El Gran Milagro and Max and Me, respectively. Similarly, the producers of For Greater Glory wanted a score very much in the Romantic tradition and actively sought out James Horner, who at that point in his career probably jumped at the opportunity to write an unabashedly large orchestral and choral score ripe with unbridled emotionality. It is a sign of these times that it took an obscure and little-seen movie about religious fanaticism for James Horner and the Golden Age tradition to shine once more.

Love’s screenplay spends the better part of an hour bringing together an interesting variety of characters and then has them interacting with each other in dramatically satisfying ways. And you have to hand it to the faith crowd: they get their musical priorities straight. In 2011 and 2017, producer Pablo Jose Barroso allotted sizable chunks of very modest budgets to the music department, allowing composer Mark McKenzie (himself a staunch Catholic) to write superlative large orchestral scores for El Gran Milagro and Max and Me, respectively. Similarly, the producers of For Greater Glory wanted a score very much in the Romantic tradition and actively sought out James Horner, who at that point in his career probably jumped at the opportunity to write an unabashedly large orchestral and choral score ripe with unbridled emotionality. It is a sign of these times that it took an obscure and little-seen movie about religious fanaticism for James Horner and the Golden Age tradition to shine once more.

Love’s screenplay spends the better part of an hour bringing together an interesting variety of characters and then has them interacting with each other in dramatically satisfying ways. And you have to hand it to the faith crowd: they get their musical priorities straight. In 2011 and 2017, producer Pablo Jose Barroso allotted sizable chunks of very modest budgets to the music department, allowing composer Mark McKenzie (himself a staunch Catholic) to write superlative large orchestral scores for El Gran Milagro and Max and Me, respectively. Similarly, the producers of For Greater Glory wanted a score very much in the Romantic tradition and actively sought out James Horner, who at that point in his career probably jumped at the opportunity to write an unabashedly large orchestral and choral score ripe with unbridled emotionality. It is a sign of these times that it took an obscure and little-seen movie about religious fanaticism for James Horner and the Golden Age tradition to shine once more.

It bears reminding what exactly Horner tried to accomplish. His score harkens back to the early days of film music, when it emerged and took root in Hollywood’s studio system that flourished in the 1930s and 1940s. The first generation of film composers were almost invariably European concert hall giants fleeing Nazi Germany. The likes of Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max(imilian) Steiner and Franz Waxman had all grown up in the musical tradition of Romanticism, which focused on emphasizing and highlighting the entire range of human emotions through the use of themes and motifs (as exemplified by Richard Wagner’s leitmotif approach) and through the use of a large symphony orchestra. In short, Romanticism was about Big Emotions. Even though by the 1920s the Romantic tradition had been rendered obsolete in the concert halls by new kinds of music, it was embraced enthusiastically by the dream factory that Hollywood aspired to be. Film Music’s Golden Age, as it came to be called, lasted into the early 1950s, fell by the wayside for nearly two decades and was rekindled by John Williams’s Star Wars in 1977. For another two decades, it would be the basso continuo of Hollywood film music, until Hans Zimmer’s rise to prominence in the early 2000s changed everything.

As evidenced by such projects as Legends of the Fall (1994) and Willow (1988), Horner the emotionalist felt very much at ease in the Golden Age methodology. When after the turn of the century film composers were increasingly asked not to reinforce the story’s emotional thrust and certainly not work with themes or melodies, which unnecessarily called attention to themselves instead of the story, James Horner slowly fell out of love with film music, which in his mind (and many others’) was rapidly becoming an impoverished art form. While only one among a host of other examples, A Bullet on the Floor is a cue that accurately represents Horner’s Golden Age manifesto. Adriana and the “women of the revolution” are on a train, carrying Cristero bullets sown into their gowns. When the train has pulled into a station, Adriana sees soldiers waiting outside and she panics. What follows is basically a scene of tension: inside the train compartment, one of the bullets falls on the floor and is picked up by an inquisitive boy a few seats away. Over the course of two intense minutes, Adriana manages to get off the train and avoids being arrested. According to present-day aesthetics, this kind of scene would be treated to a musically indeterminate cue churning in the background. James Horner, however, decided to score the panic raging inside Adriana’s mind. In doing so, he composed a full-on action cue for a scene of tension. Since this is exactly what the filmmakers had in mind and since there was little action and virtually no dialogue to contend with, the musical cue had the movie’s composite sound track all to itself and James Horner was allowed to shine.

Good news all the way then? Well, things are a bit more complicated. Since the movie overtly supports religious fanatics, since it is in the business of Big Religious Emotions and since James Horner was asked to supply Big Musical Emotions, the movie and the score share the same Achilles’ heel. If you thought Horner over-scored Tristan’s Return in Legends of the Fall, this score will have you foaming at the mouth. In context at least, because on its belated soundtrack album, James Horner’s score is a rewarding standalone listening experience that attracted mostly kind reviews and was an instant favorite among fans. But a film score can only be fully understood when it is analyzed in the context of the movie for which it was composed, and in this respect, the composer always has to work with and especially for the material at hand. Consequently, when the story turns to pathos, the music must follow suit, especially since extraverted Golden Age emotionalism was what drew Horner to the project in the first place. Boundless pathos in a highly dubious scene led James Horner to compose José’s Martyrdom, and while nothing in the score comes even close to equaling the emotional impact of that cue, making it a genuine standout set piece, it is also the most contentious cue in a score that has no shortage of them. Again, the combination of Golden Age aesthetics and a story that glorifies religious zealotry all but forced Horner to do what he did, and again, it is regrettable that at the time, For Greater Glory was the only kind of opportunity left for Horner to compose the music he so excelled at. Still, the pitfalls the composer faced were huge and he did not manage to avoid all of them.

Fortunately, there’s far more to the score than that. Had Horner been content to paint white on white, lending indiscriminate support to the violent Cristeros the way the filmmakers do, For Greater Glory quite simply would not have been a Horner score. In fact, James Horner was a shy human being and he hated violence, as evidenced by the very nature of his music and by the projects he chose to score once he was afforded that freedom (especially after 1997’s Titanic). As a result, careful analysis of the score leads one to believe that Horner, while seemingly paying lip service to the filmmakers and their religious agenda, secretly pursued an agenda of his own, and a quite different one at that. Carefully developing his own narrative, the composer subtly but unequivocally condemns the Cristeros’ violence and, in the musical portrayal of Oscar Isaac’s Victoriano Ramirez, even allows the score to become deliciously satirical.

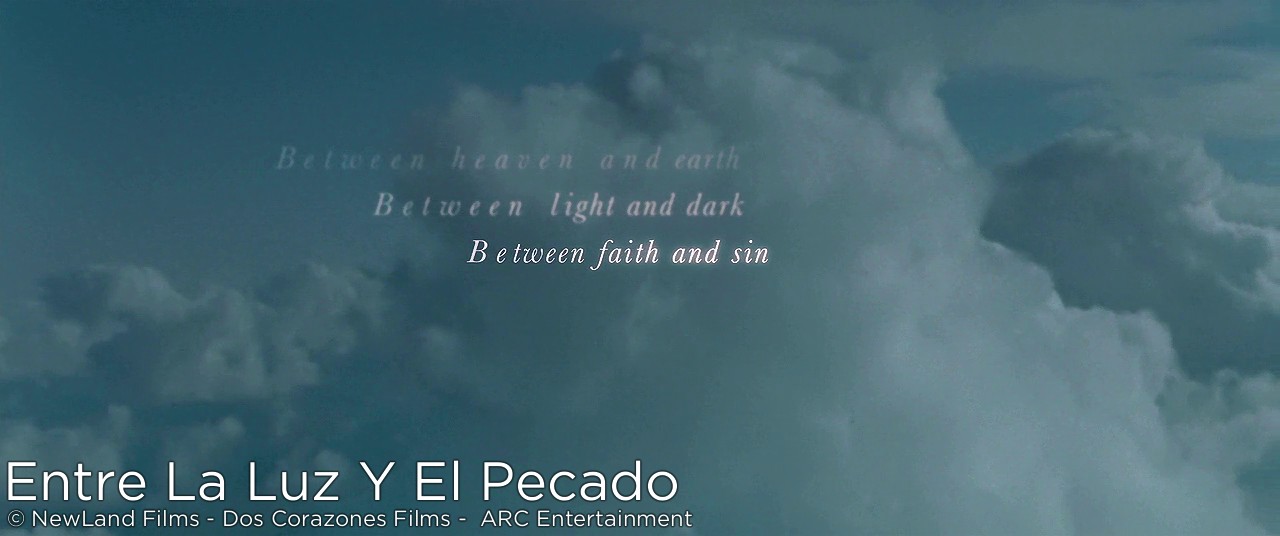

In keeping with the leitmotif approach, Horner works with no fewer than five musical building stones. For the element of faith, he composed a theme that managed to accommodate the poem opening the movie: “Entre el cielo y la tierra / Entre la luz y la oscuridad / Entre la fé y el pecado / Solo se encuentra mi corazon / Està Dios y solo mi corazon.” In English: “Between heaven and earth / Between light and darkness / Between faith and sin / There is only my heart / There is God and only my heart.” According to Clara Sanabras, James Horner himself composed the poem, maybe as an expression of the constancy of God's love and his boundless mercy for sinners. That, in spite of the fact that none of us are perfect (we are all somewhere between faith and sin, between light and dark…), God loves us and calls us to be better. The words appear over a shot of the heavens, each line like a cloud dissipated by the wind. Yet such is the power of poetry that a single poem can be interpreted in many different ways, and the thoughts expressed in this one can also be interpreted as a justification of the violence committed by the soldiers of Christ: “between faith and sin, there is only my heart, God and my heart.” In the minds of the Cristeros, faith and sin are matters solely decided between them and God. There is precious little to set them apart from other religious terrorists, who accept only God’s judgment to the detriment of the ones pronounced by earthly courts. Considering the support shown for a violent uprising, this could very well the filmmakers’ manifesto. For this theme of religion, Horner drew on the London Voices choir and especially French-Catalan singer Clara Sanabras, whose vocal work is among the score’s finest achievements.

The second theme represents Andy Garcia’s general Enrique Gorostieta, a veteran of the Mexican revolution and an atheist. Horner supplies Gorostieta with the exact same theme that soars at the very start of the end credits in The Four Feathers (2002). There, the idea denoted the pride of the (Western) military, and the association with Gorostieta immediately becomes clear.

Horner also composed a theme of rebellion, an appropriately sweeping idea that starts with a big leap up the scale followed by a series of notes in a conspicuously descending order. This theme is connected to the flying theme in Flight and The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008), similar ideas which also deal with freedom and therefore similarly structured. On the other hand, what if the successively rising and falling structure was Horner’s interpretation of the rebellion: it starts off as a high-minded affair but before long, it descends into chaos. (The Cristeros were active for about two years, when a US-brokered compromise between the Vatican and the Calles regime was reached and the Cristeros were relegated to a footnote in history.) Even though James Horner gleefully and repeatedly arranges the rebellion theme for full orchestra and triumphant cymbal crashes, the composer’s criticism of the rebellion may be evident in the melody’s basic structure. If so, this is just one of the many ways in which Horner subverts the movie’s ideology.

Apart from religion, Gorostieta and the rebellion, which are all acknowledged by genuine melodies, Horner brings into play two motifs. Both speak to the story’s darker elements, and the first is quite predictably the (in)famous four-note motif that is, in retrospect, the common thread running through the tapestry of Horner’s oeuvre. It comes as no surprise that the four-note motif is first associated with Calles, whose atheism conveniently makes him the movie’s bad guy. Far more surprising, however, is that Horner also attributes the motif, and increasingly so, to the Cristeros, thereby condemning all violence, whatever its origin. Horner’s playbook of good guys and bad guys is considerably less simplistic than the filmmakers’, especially when the composer also uses the second idea of evil for nearly everyone involved. This second dark idea is the stuff of genius. In fact, it is a succession of three descending notes for low strings and oppressive percussion that Horner first used for Titanic’s opening third, when we see the once proud ocean liner lying at the bottom of the sea, a decomposing shipwreck. The reprise of this idea in For Greater Glory is ripe with associative power. This is Horner saying that anyone who resorts to violence in difficult times is like a ship destined to end up at the bottom of the sea. I’ll call this three-note idea the sinking motif. And boy, does Horner drive the point home! When like most other fans I discovered the score on Varese Sarabande’s soundtrack album, I was almost fed up with the way the composer used the idea to end seemingly every single one of the soundtrack suites. In the context of the movie, however, Horner’s intentions become quite clear: he features it in nearly each of the movie’s set pieces, including the last minute of the movie itself and the last minute of the end title suite (the first half of which is two splendid minutes longer in the movie than on the album). And yet the origin of this motif and its obsessive use slipped past the attention of most film music critics. So abstract is the nature of music and so “unheard” by the audience is 99% of all underscore that it allows film composers to pursue their own agenda and construct their own story, which sometimes ends up telling the exact opposite of what the movie puts forward. This incredible potential of film music is utterly lost on listeners unless heard in the movie’s context, to which a score owes its raison d’être.

And Horner does not stop there. Not only does he use the motifs of darkness for both Calles and the Cristeros, he also attributes the choir to both! In fact, Horner reprises the wordless and slightly processed “ha-ha” vocals from Avatar (2009) and uses them in many of the Cristeros raids as well as an early scene in which Calles’s soldiers march down the street and wreak havoc in a church during mass. The composer first experimented with processed voices in Titanic (where they acted as ghostly echoes of the disaster’s many victims), had correctly deemed this processed and therefore strange quality appropriate for the alien worlds of Avatar and now reinterprets the same processed human voices as a metaphor for the dehumanization of this story’s many violent protagonists. All James Horner had to do was use the same idea again, but the whole art of re-using an idea is breathing new life and new meaning into it. This is Horner’s composing methodology: come up with a musical idea, nurture it over the course of successive projects and create new and surprising associations with various, even wildly divergent story concepts and ideas. In the end, what slowly emerges is not so much a number of individual scores as a carefully woven tapestry of highly polysemic musical building stones. More than in any other film composer, the whole of James Horner’s oeuvre is a lot bigger than the sum of its parts.

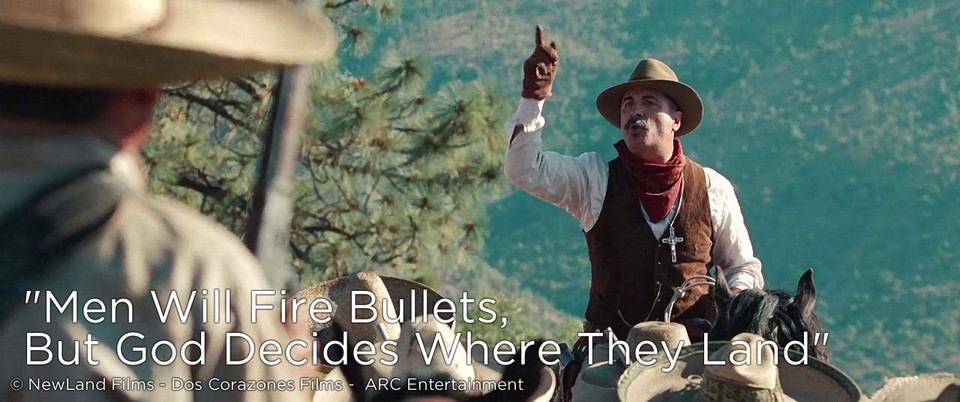

Which is probably why Horner threw in two statements of Braveheart’s Sons of Scotland theme for good measure. The first appears during Gorostieta’s big speech before the soldiers (“Men Will Fire Bullets, But God Decides Where They Land”), during which the general uses the word freedom at least three times in sixty seconds. The theme’s second statement kicks off the unreleased first portion of the end credits – curiously, this statement was available as a sound clip back when the soundtrack album was announced.

Once the Golden Age composer has settled on his thematic and motivic building stones, he can go to work and compose the score proper. During this part of the composing process, and true to the tradition to which he knew he belonged, James Horner reached deep into the toolbox of musical tricks to help tell the story and express the characters’ thoughts and motivations. Horner always focused on character rather than story, so let us bring the various protagonists into focus while pointing to the composer’s many diversions from the movie’s ideas.

Taken together, the Mexican president Calles (Rubén Blades), the American ambassador to Mexico, Dwight Morrow (Bruce Greenwood) and one particularly sadistic Mexican officer constitute the authorities. Since the screenplay has precious little to say in their favor, Horner scores their scenes mostly with the four-note and sinking motifs. In fact, ambassador Morrow was sent to Mexico by president Calvin Coolidge (Bruce McGill) to fix the problem of the oil field concessions, and in a display of political horse trading, Morrow offers Calles the US air planes and military equipment he desperately needs to stamp out the Cristeros in exchange for a more favorable ruling on the Bucareli treaty. In the end, though, Morrow brokered a compromise between the Vatican and Calles which made it possible for Mexican priests to say mass in public again, but which also meant the Vatican turned its back on the Cristeros. Still, a number of Cristero protagonists were later beatified or canonized, especially under Pope John Paul II.

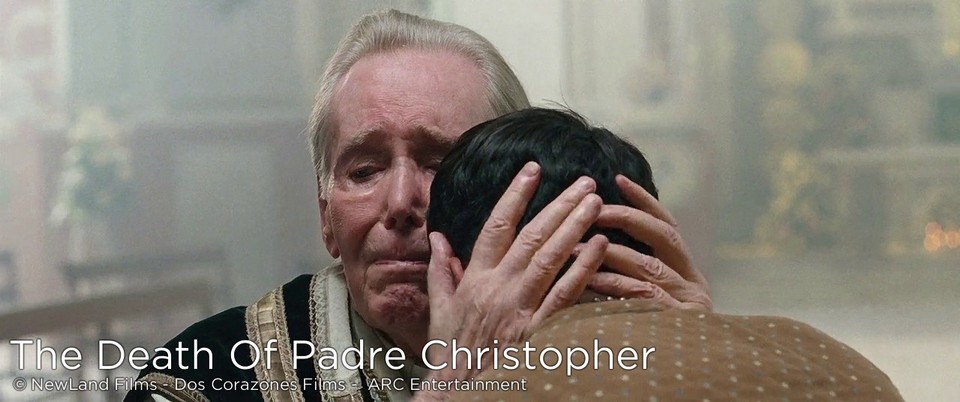

Since he goes through the most significant transformation arc, Enrique Gorostieta is the movie’s de facto protagonist. When he walks into the story with his wife Tula (The Desperate Housewives’ Eva Longoria) and his two daughters, he is an atheist ex-general who is fairly indifferent to the brewing religious unrest. All the same, Gorostieta is a military man, and now that the revolution is over, he is reduced to overseeing production in his soap factory, a prosperous new purpose in life that nevertheless leaves him deeply unfulfilled. When he is approached by the League of Cristeros, his initial response is disbelief: how could anyone mistake him for a man of faith? On the other hand, the Cristeros war offers the perspective of a return to the glories of the battlefield and the cunning of strategy and warfare. His Catholic wife Tula sends him off hoping the gig will turn him into a believer (!) and Gorostieta abandons her with the (false) promise that he will come back, at which point Horner ends the cue with an appropriately dark chord. Gorostieta leaves his old life behind and redirects his military skills to serving the Cristeros’ cause. Through a series of poorly scripted revelations, the atheist becomes a believer, especially after meeting José, a ten-year-old boy whose faith was triggered by Father Christopher (Peter O’Toole), who had taken the boy under his wing and started training him as an altar boy before being summarily executed by Calles’s soldiers. Even though Father Christopher was a pacifist, his brutal death stirred other sentiments in José’s heart, who at this tender age shows all the characteristics of a soldier of Christ. José’s unshakable faith is not lost on Gorostieta, who tells one of his aides that “the young boy inspires me”. Moreover, as he tells the boy himself: “I’ve never had a son, but if I did, I would want him to be like you.”

Horner gets his priorities straight. The aforementioned prologue meant he had to start the score with the religion theme, but in the next shot, Horner segues to Gorostieta’s theme instead of the rebellion theme, which would have been more appropriate given the title cards detailing the historical context in which the Cristeros emerged. Whether conscious or not, this choice is indicative of Horner’s own manifesto: character over action and concept.

Back in 2012 and without having seen the movie, most film music critics identified Gorostieta’s theme as the score’s love theme. While Horner makes extensive use of the melody in Goro and Tula, the attribution goes a lot further than that. In the film, the general leaves his wife and daughters at the forty-minute mark and the family never return to the story. In the second part of the movie, the theme’s attribution evolves. It spends a while linked exclusively to Gorostieta himself, but as the general develops a fatherly love for José, the son he never had, the theme is increasingly performed by the instrument James Horner had first used to identify José, an appropriately fragile ethnic flute. The father’s theme performed by the son’s instrument, it’s a wonderful musical way to tie both characters together. At 1:45:24, Picazo, the boy’s godfather and mayor of the village, tries to save the captured boy from hanging. He stops the soldiers, embraces José and says: “I’m going to take you home now.” With godfather Picazo becoming José’s new protector, Horner again changes gears and, for the briefest of moments, Gorostieta’s theme becomes a fatherhood theme. When José refuses to renounce his faith and proudly recites the Cristero rallying-cry “Viva Cristo Rey!”, the fatherhood theme is abruptly broken off by the tolling of a church bell as Picazo walks away and abandons his godson, whose fate is now sealed.

Further proof that James Horner did not embrace the Cristeros’ cause comes in the use of the rebellion theme. In fact, its first appearance (at 11:37 into the movie) is conspicuously linked to the idea of an economic boycott an older man suggests to Adriana while she is out encouraging people to sign her petition. This happens during the comparatively short first act, when similar (real-life) characters like Father Christopher and Anacleto Gonzalez Flores speak out against violent protest. Between 21:25 and 21:53, Father Christopher is about to be arrested and executed, and he tells José to run away. Playing under these thirty seconds, the rebellion theme comments on a moment which is anything but a rebellion on behalf of either character. By applying the rebellion theme to economic resistance and to the acceptance of an impending death, Horner poisons the theme’s roots before he is required to drape it with grandiose orchestrations for, say, Gorostieta’s final stand. When Gorostieta first meets the Cristero leadership (at 57:10), he confronts Father Vega with a cruel mistake that took 51 innocent lives, and Horner presents a restrained, solemn and somewhat depressed horn statement of the rebellion theme as Vega is forced to acknowledge that he is driven by revenge, not the pursuit of freedom. At 58:00, the rebellion theme appears in a more stirring setting, complete with swirling strings as Gorostieta delivers his first galvanizing speech, but when in the very next scene José’s older brother Miguel is hanged from a tree, Horner returns to Gorostieta’s theme. Although the general is not present in this scene, the echo of his preceding speech hangs over it, a subtle warning that he too will bring death. During Gorostieta’s big speech in front of the soldiers later on, Horner slips in a short suggestion of the four-note motif (at 1:29:00) just before the score’s first statement of the Sons of Scotland theme. When prior to his last stand, Gorostieta wants to confess in a belated attempt to become an official Catholic, Horner responds with uneasy strings punctuated by insistent and repeated statements of the four-note motif, foreshadowing the general’s death but also draping the confession scene in a dark veil. (It is the first part of the climactic Cristeros cue.)

Victoriano Ramirez (Oscar Isaacs) is an interesting character. He is a man of action, not necessarily faith, and he is introduced during a raid against Mexican soldiers. Victoriano leads a ragtag band of rebels and initially has no intention of subjecting himself to Gorostieta. At one point, he ignores the general’s advice and takes his men into the Tlaquepaque canyon, where he is ambushed by Calles’s men. Gorostieta had a gut feeling about the ambush and comes to the rescue, earning the rogue’s respect. Later, José gives his horse to a then wounded Victoriano, who leaves the boy in the middle of the battle, at the mercy of the soldiers. Overcome with grief and guilt, he subsequently turns to God for comfort and finds faith.

Ever since getting out of an ambush and killing fourteen soldiers in the process, Victoriano is nicknamed El Catorce by his men. In his first scenes, he kills indiscriminately and gleefully. Horner reinterprets El Catorce, for whom war is seemingly a game, as Zorro-turned-religious-fanatic and surrounds him with material conspicuously reminiscent of The Mask of Zorro (1998) and The Legend of Zorro (2005): hints of action riffs, a playful guitar and the religion theme performed by the trumpet, the instrument that best and most often characterized Antonio Banderas’s sly fox. At 34:04, a brass build-up straight out of Zorro leads to a triumphant statement of the rebellion theme (at 34:12) where any Horner fan would have expected the Zorro theme. By placing the religion theme in an almost playful action setting (We’re Cristeros Now), the composer robs it of its solemn tone, thereby subverting the lofty ideas it stands for. Of course, satire does not work unless it has some bite, and Horner never loses sight of the four-note and sinking motifs. Unwilling to acknowledge the success that the catorce slaughter represented for Victoriano, Horner leaves that scene unscored, which makes it stick out like a sore thumb in a movie scored almost wall-to-wall. The Zorro reference resurfaces at 39:09, when Victoriano and his men enter Vega’s camp and Horner treats them to a kind of pompously heroic grandeur that would almost have been too big for Zorro himself! However, the cynical war hero becomes a humble Catholic when he realizes he has abandoned young José. At 1:34:35, Horner again moves the religion theme to Zorro’s trumpet. Only this time, there is no ethnic or orchestral accompaniment, and the trumpet sounds desperate and forlorn. Finally, at the battle of Tepatitlàn, Victoriano is killed. His farewell scene is accompanied by Zorro’s guitars, but the religion theme is now handed to plaintive strings. While El Catorce draws his last breath, Horner bids him adieu with a wonderfully subtle Zorro-esque flourish in those very strings (1:42:26). Even in satire, James Horner could not resist an opportunity to infuse characters with a degree of humanity. At any rate, the Zorro references make Victoriano’s character infinitely more interesting.

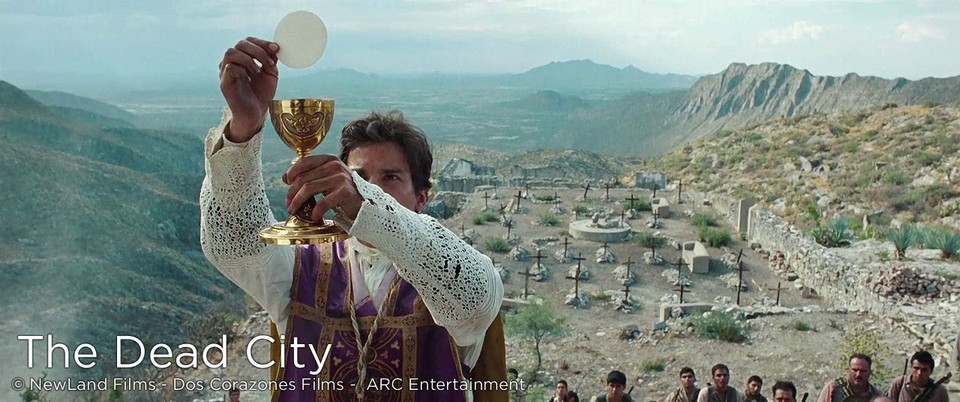

In a themes-and-variations score, part of the fun is finding out where the composer plays which theme and why. James Horner was a master at using thematic material to express what goes on inside a character’s head, and this score features a myriad of wonderful examples. When from a secret passageway Adriana sees her beloved Anacleto stabbed by soldiers, the religion theme is there to comfort her. When after the discovery of The Dead City, the Cristeros bury their dead and father Vega says mass, a still atheist Gorostieta is isolated from them but the religion theme signals faith growing inside his mind. When Father Vega (now a general) accidentally burns 51 passengers after taking one of Calles’s gold trains, the religion theme is heard (at 52:35) in badly fragmented form, while soft wordless voices echo the cries of the burning victims. An endearing oboe statement of the religion theme plays over gently moving strings as young José sweeps the floors of Father Christopher’s church and is ever more intrigued by the place.

And this brings us to the score’s standout set piece, the elaborate death of the child José, for which Horner composed José’s Martyrdom and Death, two cues that could not be more different. The filmmakers present José’s final moments as the Christ’s way to the cross: there’s torture (the sadistic Mexican officer slices José’s feet with a knife), there’s the road to Golgotha lined with bystanders, there’s the slow and painful procession of José trying to keep up on bloody feet while surrounded by soldiers escorting him to the site of the cross (which in this case is a hole dug in the ground). At one point, José falls as Jesus did, and turns down a soldier offering a hand to help him back up again. At the scene of the execution, a thunderstorm erupts (it’s probably three o’clock in the afternoon by then), José’s mother, dressed up as the Virgin Mary, smiles down upon her son with sadness and silent admiration, you name it, it’s all there. Just before being stabbed to death, José smiles back and says one last time: “Viva Cristo Rey!”

What makes this scene preposterous and absurd is that the biblical character of Jesus was thirty-three instead of nine, Jesus was the son of God (and therefore the concept of pain was also of a more transcendent nature) and Jesus knew full well what he was going through because he knew he had been sent to bring a sacrifice of blood that would wash away man’s sins, a divine mandate which José was never granted. But most of all, the scene suffers from a total lack of believability: a ten-year-old boy paraded through town before being stabbed in the back, with his godfather, his sister and his biological parents content to be stoic bystanders?

Still, from Gorostieta’s perspective this is the big All Is Lost moment and James Horner owed it to the general’s transformation arc and to the pursuit of scoring Big Emotions to go all-out with the religion theme, which is exactly what José’s Martyrdom does. The resulting pathos is so bloated that many viewers will find it offensive in context. All the same, the emotional impact of the piece is not to be underestimated. Moreover, the cue plays like a self-contained musical entity. Its evolution is linked to the visuals through a number of sync points but Horner has carefully preserved the organic flow, which means it can also be listened to as a standalone concert piece. (In fact, during the 2012 Cordoba Film Music Festival in Spain, the piece was performed by the Cordoba Orchestra conducted by Blake Neely.)

During the first section (1:57:03 – 1:58:22) Clara Sanabras softly sings a complete statement of the religion theme as the words are supposed to reflect precisely what the young martyr is going through while his feet are being sliced. The lone oboe in between is James Horner taking pity on the boy. At 1:58:22, we cut to Gorostieta and his men hunched over a map, plotting their next attack. Lalo, José’s young friend, interrupts the proceedings, tells the general where José is and what is happening to him. As Gorostieta swings into action, a solemn statement of his theme is accompanied by militaristic snare drum. At 1:58:50, the snare drum figure turns into an oppressive dirge-like rhythm over which Sanabras reprises the religion theme, but now her tone is confident, defiant even, backed by the rest of the choir and as many orchestra players as the moment could possibly stand. This is the central part of the cue, and it scores the way of the cross itself, as José walks up the street in slow-motion. At 1:59:21 we see José’s sister watching from a balcony and Horner segues to a heartbreaking interlude for what sounds like a boy soprano. In fact, this is still Clara Sanabras singing in a very high range. She was reportedly so out of breath on the last two notes she could barely keep singing. You can hear her taking a short breath before the final note. James Horner apparently liked it so much that he did not want her to do another take. To him it became a spur-of-the-moment acknowledgement of Jose and him taking his last breath. That he loved imperfections in performances or labored breaths and the sounds of fingers on strings and frets shows James Horner’s very real sense of connection to the musicians and their performances of his organic, living music but it also attests to the intimacy of his storytelling.

At 2:00:12, an overhead shot follows José and reveals the hole in the ground, at which point Horner introduces a tolling bell. Playing underneath is not the four-note motif, but, interestingly, the sinking motif, Horner’s lone personal commentary. Where the filmmakers see the rise of a martyr, James Horner sees only human loss. The last tolling bell accent is for Picazo, who begs his godson one last time to renounce his faith and respectfully takes off his hat.

A good half minute passes unscored before at 2:01:19, the sadistic officer stabs José in the back. In more ways than one, Death is the polar opposite of José’s Martyrdom. Interestingly, Horner scores the stabbing exactly like he scored the moment when William Wallace is disemboweled at the end of Braveheart: not with a stinger or a violent accent, but with soft strings slowly easing in. Gone is the pathos, this is a cue of refreshing restraint. The religion theme makes another appearance and at 2:01:33, it is again taken up by solo voice, but this time around, Sanabras is humming, not singing, as the dying José draws a bloody cross into the sand before being pushed into the hole.

Gorostieta and his men arrive at the scene and shoot down all the soldiers. The filmmakers wisely decided not to break the tone of the piece: the music continues its soft lament while the shots fired are totally silent. Until the last one, which shatters the serenity of the moment as attention shifts away from José and back to the general. At 2:02:37, Horner appropriately brings in Gorostieta’s theme. He takes José’s body out of the hole and embraces him. At 2:03:02, Horner returns to the religion theme as the general kisses José’s cheek and hands the body back to the mother (again, like the body of Christ in Mary’s lap) and this is where one of the finest moments of the entire score occurs. Having given the child back to its biological parents, Gorostieta is now left utterly alone and cut off. Horner expresses this with a musical moment that is as simple as it is inventive: he uses both the religious theme and Goro’s theme in conjunction, but little by little, the themes disconnect from each other. The union between faith and Gorostieta unravels as the general’s theme unravels, descending into ever lower and darker chords. (It’s the start of Gorostieta’s Dark Night of the Soul, which in this case takes the form of a deep crisis of faith.)

Death is everything José’s Martyrdom is not: it is respectfully restrained, it uses themes in intelligent ways and it does not paint white on white. Instead of shoving the point down the audience’s throat, Horner supplies nuances and meanings that are nowhere to be found onscreen, but which emerge from the wondrous marriage between music and visuals. Together, José’s Martyrdom and Death are a formidable pair of cues that take the drama to dizzying heights. More importantly, they are a fascinating metaphor for the dichotomy that lies at the heart of the score. Horner walked a tightrope, scoring the action and the drama up to the hilt whenever it was required of him or whenever the opportunity presented itself, while at the same time going off on a narrative of his own, which afforded the much-needed chance for comment, nuance and criticism. In this respect, one might wonder what the score’s main theme is, since Horner uses the religion, Gorostieta and rebellion identities in equal quantities. If the number of thematic statements is anything to go by, then the score’s main themes are undoubtedly the four-note and sinking motifs, and this goes a long way toward explaining James Horner’s interpretation of the piece. The filmmakers aim for God, James Horner never loses sight of the characters. Where the filmmakers see religious fervor, James Horner sees human suffering. The score composed for Cristiada is not the work of an ardent believer or an unforgiving atheist, but a multi-layered meditation by a tender-hearted humanist.

![[REVIEW] JAMES HORNER: A LIFE IN MUSIC AT THE ROYAL ALBERT HALL](https://jameshorner-filmmusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Life-in_music-1024x487.jpg)

Wow, For Greater Glory-a wonderful score and notes to bring Remembrance Week 2018 to a close. I am playing this music right now, it has become one of my favouriite JH scores, apart from it being very special to me because of the musical friends I have made since it’s release. It is such a beautiful melody….as also played by Mari & Hakon Samuelsen (Jose’s Martyrdom) on COLLAGE-the last work.

We all wish the events on that tragic day back in 2015 had never happened but James’s music will live on and on with the devoted JHFM team doing such a tremendous job to fulfill his legacy. I thank you for all of your pieces this past week. Pamela.

I think the movie is not at all about “religious fanaticism” as you state in the article. The Christian characters are also not fanatics but rather persecuted people who simply decide to fight for their lives and for their faith. (Honestly, the Jewish people of the Warshaw uprising were fanatics because they fought for their lives? I don’t think they were. Just as Braveheart is not about some fanatic Scots who oppose the great and loving British king and his army.) The real fanatics in this movie are the Mexican government and their soldiers.

I think Horner understood this very well and created a wonderful score that depicts faith, courage, fight, tragedy and love in equal measure. This movie is not pro-violence at all and I believe Horner got it from the start.