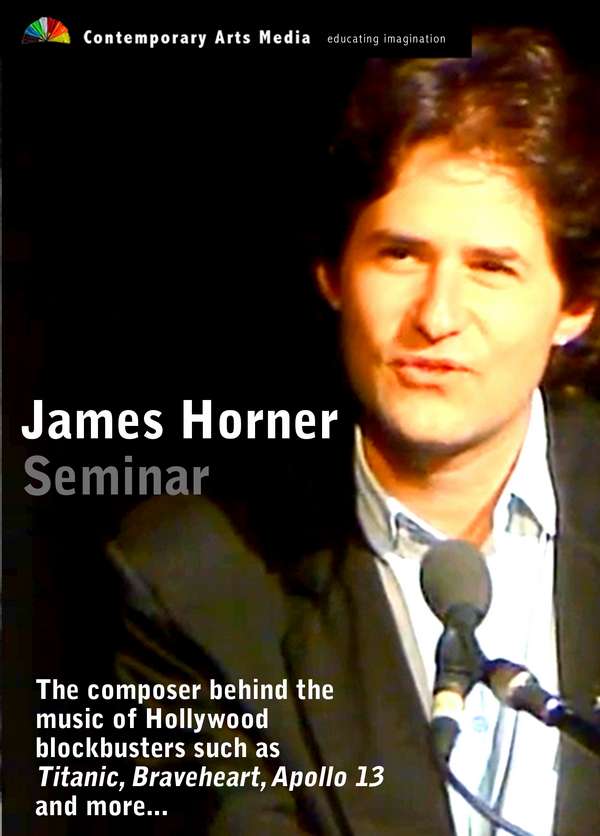

[divider] James Horner Seminar – Artfilms [/divider]

Special thanks to Kriszta Doczy (Art Films)

To access the full seminar, you can purchase the DVD or access to streaming online by following this link: Purchase James Horner Seminar – Artfilms

Maestro, tell us about you.

Thanks for having me here and I'm very flattered that you would have me here. I'm sort of surprised there is so much interest about film music, because usually it's sort of an artform which is very much behind the scenes. I mean people know about directors and editors, and certainly movie stars, but music, almost nobody knows how it's put together. In fact, one women once asked me whether I was in charge of selecting the records that are used in movies, you know, because she thought that all music came off of records and it didn't even occur to her that anything was composed.

Really!

Absolutely. So, I started off my career with a conscious decision not to do television, when I decided to go into writing music for film, as it were, as opposed to serious music  (concert music). I started off writing music for the American Film Institute, which is also called AFI. I did about seven or eight student films, then I got a job scoring some very low budget films for Roger Corman who was sort of the king of B-movies in Hollywood through the 50's, 60's and into the 70's. I think I did like seven films for him, things that are now sort of, I guess, cult classics, but at the time were sort of horrible to do. I got very little money, in fact no money. He basically would give me a fee of about $8,000 or $10,000 and say: "James, make the score." That was my fee and that was the musicians’ fee. The whole thing was very, very little money and no money went to me, and I would pour it all into doing the score. But that sort of set me up with a school, that I learned all kinds of things that I never would have learned had I done television.

(concert music). I started off writing music for the American Film Institute, which is also called AFI. I did about seven or eight student films, then I got a job scoring some very low budget films for Roger Corman who was sort of the king of B-movies in Hollywood through the 50's, 60's and into the 70's. I think I did like seven films for him, things that are now sort of, I guess, cult classics, but at the time were sort of horrible to do. I got very little money, in fact no money. He basically would give me a fee of about $8,000 or $10,000 and say: "James, make the score." That was my fee and that was the musicians’ fee. The whole thing was very, very little money and no money went to me, and I would pour it all into doing the score. But that sort of set me up with a school, that I learned all kinds of things that I never would have learned had I done television.

(concert music). I started off writing music for the American Film Institute, which is also called AFI. I did about seven or eight student films, then I got a job scoring some very low budget films for Roger Corman who was sort of the king of B-movies in Hollywood through the 50's, 60's and into the 70's. I think I did like seven films for him, things that are now sort of, I guess, cult classics, but at the time were sort of horrible to do. I got very little money, in fact no money. He basically would give me a fee of about $8,000 or $10,000 and say: "James, make the score." That was my fee and that was the musicians’ fee. The whole thing was very, very little money and no money went to me, and I would pour it all into doing the score. But that sort of set me up with a school, that I learned all kinds of things that I never would have learned had I done television.

(concert music). I started off writing music for the American Film Institute, which is also called AFI. I did about seven or eight student films, then I got a job scoring some very low budget films for Roger Corman who was sort of the king of B-movies in Hollywood through the 50's, 60's and into the 70's. I think I did like seven films for him, things that are now sort of, I guess, cult classics, but at the time were sort of horrible to do. I got very little money, in fact no money. He basically would give me a fee of about $8,000 or $10,000 and say: "James, make the score." That was my fee and that was the musicians’ fee. The whole thing was very, very little money and no money went to me, and I would pour it all into doing the score. But that sort of set me up with a school, that I learned all kinds of things that I never would have learned had I done television.

Could you give us a little background on the fundamental method that you adopt in Hollywood or that you have to adopt yourself into?

Usually the film is still being edited when I am asked or hired to do the film. I almost always ask to see the film because I can't really tell what the film will be like based on just a script. I turned down Field of Dreams based on a script and the filmmaker came back to me when the film was shot, which is very rare. Usually if you turn down something, that's it. And it was a wonderful film. But I tend to make my film decisions based on something I can see rather than something I can read, because so much can change, as I'm sure you all realize.

The process is one where basically once I've decided to do a film, I look at it a couple of times on my own of course. Then the director and I, and sometimes the producer, or often producers, depending, and an editor will sit down in a room with a film projector and we'll project the film and look at the film reel by reel. From Reel 1 all the way through Reel 12, or 14, or 16, however many reels there are. We will decide where music starts, where it ends, what it's going to do while it's happening, what are the salient ideas the director wants brought forward, what he wants me to catch with the music: that is, what he wants me to accentuate with the music. All of these things are discussed. And this session is called a spotting session, and it's really where music is spotted in the film. Each piece of music is referred to as a cue. So we'll start, we'll sit down, and they'll start rolling Reel 1 and usually at the head of Reel 1 is the corporation logo, let's say Twentieth Century Fox, so you have a fanfare, OK. My first question will be: "Do we have permission to play the fanfare silent or is Twentieth Century going to insist we have the music with the fanfare?" Because as a composer, obviously you have this huge brass fanfare and the next scene is the first frame of the movie. How do you musically do that? I mean it's difficult to sort of make the musical transition. So I tend to think about all of these things.

And after?

We'll discuss that and we'll discuss how the main title, the first cue of the film over the titles, is going to work. How it's going to go, where it's going to end. Then the next cue. And we just go through reel by reel and my editor is making a note on a piece of paper of all the start footages and end footages of each sequence. Well, then at the end of the spotting session, which can take one or two days, he will go to his place and he will convert all those timings to seconds, usually hundredths of a second. So he'll say that starting at 00:00 time the sequence starts and it goes through 12:31. 7 seconds. And then he will give me the breakdown of what happens in time all through that 12 minute sequence. Then I write the music and as I'm going I make these notations or special marks at the top of the page which are synchronization marks. And my editor, when he gets my score after I've written it, I'll send him a copy and he will take those marks and he will scribe his film literally with a steel pin.

We'll discuss that and we'll discuss how the main title, the first cue of the film over the titles, is going to work. How it's going to go, where it's going to end. Then the next cue. And we just go through reel by reel and my editor is making a note on a piece of paper of all the start footages and end footages of each sequence. Well, then at the end of the spotting session, which can take one or two days, he will go to his place and he will convert all those timings to seconds, usually hundredths of a second. So he'll say that starting at 00:00 time the sequence starts and it goes through 12:31. 7 seconds. And then he will give me the breakdown of what happens in time all through that 12 minute sequence. Then I write the music and as I'm going I make these notations or special marks at the top of the page which are synchronization marks. And my editor, when he gets my score after I've written it, I'll send him a copy and he will take those marks and he will scribe his film literally with a steel pin.

There are really two basic ways, as you write music, how you synchronize it to picture. As you're writing you have a book of timings and you choose a tempo for yourself and you look in the book that on beat 325 it's such-and-such a time, and you're able to work out the maths of the music to the picture by these sort of complicated book of tables.

The way a composer conducts an orchestra, they either use a process by which is called click tracks, where in the headset of all the musicians is a beat that's going by, and the conductor is conducting the beat, and everybody is hearing that, and they are all playing, and you always know that on the 342nd beat it's going to be at such-and-such time, and it's a way of synchronizing. I use a slightly more old fashioned system. I don't like click tracks, I don't find it particularly musical.

Where I make indications on my score and my editor takes those indications and marks them on the film. So if you're the conductor and I'm the orchestra and the picture is playing, you'll be conducting and looking at the score and you'll see the same marks on the screen, you'll be able to ebb-and-flow get ahead of yourself or behind the marks. That's what gives the music it's sort of ebb-and-flow. It works very well and it's a very fluid system. The click track system tends to be fixed and of one tempo.

When we were discussing just a second ago of how many hit points or how many things are structurally matched between the score and the picture. For somebody like George Lucas, which Willow was made, George likes a lot of things in the music to accentuate the picture. Like when they go over the rock and go off the ledge. He wants dozens and dozens of things caught, they're called "catches". It ends up being very difficult to write really wonderfully lyrical music when you're always having to accentuate what picture does. But you get the knack of sort of working within the system and not being bound by the tools.

When we were discussing just a second ago of how many hit points or how many things are structurally matched between the score and the picture. For somebody like George Lucas, which Willow was made, George likes a lot of things in the music to accentuate the picture. Like when they go over the rock and go off the ledge. He wants dozens and dozens of things caught, they're called "catches". It ends up being very difficult to write really wonderfully lyrical music when you're always having to accentuate what picture does. But you get the knack of sort of working within the system and not being bound by the tools.

The way a composer conducts an orchestra, they either use a process by which is called click tracks, where in the headset of all the musicians is a beat that's going by, and the conductor is conducting the beat, and everybody is hearing that, and they are all playing, and you always know that on the 342nd beat it's going to be at such-and-such time, and it's a way of synchronizing. I use a slightly more old fashioned system. I don't like click tracks, I don't find it particularly musical.

Where I make indications on my score and my editor takes those indications and marks them on the film. So if you're the conductor and I'm the orchestra and the picture is playing, you'll be conducting and looking at the score and you'll see the same marks on the screen, you'll be able to ebb-and-flow get ahead of yourself or behind the marks. That's what gives the music it's sort of ebb-and-flow. It works very well and it's a very fluid system. The click track system tends to be fixed and of one tempo.

When we were discussing just a second ago of how many hit points or how many things are structurally matched between the score and the picture. For somebody like George Lucas, which Willow was made, George likes a lot of things in the music to accentuate the picture. Like when they go over the rock and go off the ledge. He wants dozens and dozens of things caught, they're called "catches". It ends up being very difficult to write really wonderfully lyrical music when you're always having to accentuate what picture does. But you get the knack of sort of working within the system and not being bound by the tools.

When we were discussing just a second ago of how many hit points or how many things are structurally matched between the score and the picture. For somebody like George Lucas, which Willow was made, George likes a lot of things in the music to accentuate the picture. Like when they go over the rock and go off the ledge. He wants dozens and dozens of things caught, they're called "catches". It ends up being very difficult to write really wonderfully lyrical music when you're always having to accentuate what picture does. But you get the knack of sort of working within the system and not being bound by the tools.

Slightly similar to scoring for animation, I assume.

Yes, It is. There's a Hollywood expression which is called Mickey Mousing which comes out of early animation. It is literally in animated movies or shows, whether it be Rocky & Bullwinkle or Bugs Bunny or whatever it is, you have all these cute cartoons which change or whatever, Porky Pig slapped in the face and the music changes and then he opens the door and the music changes. All of those changes happen very rapidly in animation. In feature films you have the same kind of changes happening, and depending on the sensibilities of the composer or the director, you will either notice them or you won't notice them. And George Lucas, as like Star Wars, has tons of those things. Every character he wants accentuated in its own particular fashion. When somebody's running, he likes that to have a different feeling than when somebody's walking. So you have to be very clever that it doesn't sound like a cartoon when you're done.

Do you have your own editor that you take to every session or does the studio supply it?

I have a fellow who I work with who is a musical editor. The studio supplies him, pays him, but it's somebody of my choosing. The Hollywood system allows me to hire a music editor. By union rules you have to have a music editor. It's one of those positions like the teamsters union where you have to have a driver for every actor and actress. You have to have a music editor. Now, sometimes you don't and they get around it. But in my case I always insist on using somebody because a music editor can be invaluable in not only the preparation of the score in terms of film synchronization, the marks, all of that, but after you're done recording and mixing he has to cut that piece of film, that stretch of music, and lay it into the film and get it just right so it's perfect. Then he supervises the music through the dub, through the mixing. So that's a fellow that's supplied by the studio, but usually they will defer to who it is I want to use.

You have one specific person that you use?

I have one specific person that, we're just good friends and we've worked together for like four years. He's about 58 years old and was the original music editor during the very first Star Trek series, television series. He comes from television. He's been around and has worked with almost every composer. We've just sort of worked out, my schedule is such that he doesn't have time to work with anybody else. His name is Jim Henrikson.

How do you Compose?

I literally write at a desk with 36 staff paper and I occasionally will try out things on the piano, but not very often. To me, I use this analogy of like a spider web. There's so many ways you can change fragments of themes and stuff that I just find it's much easier to just sort of, as if you're closing your eyes, just go straight to paper, it takes a great amount of concentration for me. It's not easy, I can't work in traffic, I can't work with a radio going, I have to be just holed up in my studio and the door shut and the phones turned off. It just takes a great deal of concentration, but that's how I work. I just sit at a desk, page after page pretty much. Then I'll check the sequence, I'll take the score and I'll look at it against the video cassette that I keep as a reference. I don't use a Moviola, I use video because the video doesn't make a sprocket noise going through, so it's quieter. And it's instant rewind and it's great. Then I'll double check my scores and that's pretty much how I put it together.

it's much easier to just sort of, as if you're closing your eyes, just go straight to paper, it takes a great amount of concentration for me. It's not easy, I can't work in traffic, I can't work with a radio going, I have to be just holed up in my studio and the door shut and the phones turned off. It just takes a great deal of concentration, but that's how I work. I just sit at a desk, page after page pretty much. Then I'll check the sequence, I'll take the score and I'll look at it against the video cassette that I keep as a reference. I don't use a Moviola, I use video because the video doesn't make a sprocket noise going through, so it's quieter. And it's instant rewind and it's great. Then I'll double check my scores and that's pretty much how I put it together.

it's much easier to just sort of, as if you're closing your eyes, just go straight to paper, it takes a great amount of concentration for me. It's not easy, I can't work in traffic, I can't work with a radio going, I have to be just holed up in my studio and the door shut and the phones turned off. It just takes a great deal of concentration, but that's how I work. I just sit at a desk, page after page pretty much. Then I'll check the sequence, I'll take the score and I'll look at it against the video cassette that I keep as a reference. I don't use a Moviola, I use video because the video doesn't make a sprocket noise going through, so it's quieter. And it's instant rewind and it's great. Then I'll double check my scores and that's pretty much how I put it together.

it's much easier to just sort of, as if you're closing your eyes, just go straight to paper, it takes a great amount of concentration for me. It's not easy, I can't work in traffic, I can't work with a radio going, I have to be just holed up in my studio and the door shut and the phones turned off. It just takes a great deal of concentration, but that's how I work. I just sit at a desk, page after page pretty much. Then I'll check the sequence, I'll take the score and I'll look at it against the video cassette that I keep as a reference. I don't use a Moviola, I use video because the video doesn't make a sprocket noise going through, so it's quieter. And it's instant rewind and it's great. Then I'll double check my scores and that's pretty much how I put it together.

Do you work with temp tracks ever?

Yes. My attitude towards temp tracks is perhaps different than most composers. I really think they are useful. They're useful in two respects. When I look at the movie I want to be swept away by the movie as much as anybody, and what better way than to have it as complete as possible. I'm like the dumbest executive when I watch it. You know, I'd like to see the movie. But the other more important thing about temp music is it gives me an indication of what the director has in mind. And what's important about that is that it makes me see whether he knows what his scene is about or whether he's asking music to sell something that's not there on screen. It's my first warning sign as to whether he's in tune with what the film is. Like if he has a visual that to me is horrifying and he's put on a love waltz or something. I'm using again a garish example, but it's a good indicator that he doesn't quite know what's going on in the film or he wants to sell something to an audience that the audience is never going to buy because the graphic is too strong on the picture. It's a great indicator for me of what the director has in mind and it's a great starting point for conversations, because I can say: "Do you really want that kind of music there? What was your reason?" And then he'll get into his explanation and then you'll get into yours. It's a very good place to start talking about music.

It's important for directors.

Directors very often get hooked on temp tracks, but it's a risk that is worth taking. They get hooked on temp tracks when they don't hear  something that comes up to the original. But usually, somehow, they put that behind them when they get in the recording session and they hear the real music that's going to be in the film. It's only very rarely that I have problems with a director saying: "I like the temp track, that wasn't like the temp track". And it's really a case where the director is not wrong, per se, but the director has become emotionally married to something he could never have, and he hasn't faced that. Short of buying the piece of music which is usually not going to happen anyway.

something that comes up to the original. But usually, somehow, they put that behind them when they get in the recording session and they hear the real music that's going to be in the film. It's only very rarely that I have problems with a director saying: "I like the temp track, that wasn't like the temp track". And it's really a case where the director is not wrong, per se, but the director has become emotionally married to something he could never have, and he hasn't faced that. Short of buying the piece of music which is usually not going to happen anyway.

something that comes up to the original. But usually, somehow, they put that behind them when they get in the recording session and they hear the real music that's going to be in the film. It's only very rarely that I have problems with a director saying: "I like the temp track, that wasn't like the temp track". And it's really a case where the director is not wrong, per se, but the director has become emotionally married to something he could never have, and he hasn't faced that. Short of buying the piece of music which is usually not going to happen anyway.

something that comes up to the original. But usually, somehow, they put that behind them when they get in the recording session and they hear the real music that's going to be in the film. It's only very rarely that I have problems with a director saying: "I like the temp track, that wasn't like the temp track". And it's really a case where the director is not wrong, per se, but the director has become emotionally married to something he could never have, and he hasn't faced that. Short of buying the piece of music which is usually not going to happen anyway.

Do you present your music before the recording? And if so, how?

I usually meet once or twice every two weeks with the director and I'll literally just put the music up on the piano and play it from the score, the orchestral score. And I'll do a lot of speaking. I'll say: "Well this will be in the such and such, or this will be in the oboes, or this will be in the strings, or this will be in chorus". What's much more difficult is when I have an abstract score that's electronic, then I can't really mock up anything.

And for songs?

How do I approach writing some of the songs that I've had to write for some of the animated movies as opposed to score? The way that has to work, there's such a long lead time in animation, like 2 1/2 years from when they start to when it ends up being on the screen. And with songs you're going to get character lips that move. So you have to write the song and the animation is done to the song.

To access the full seminar, you can purchase the DVD or access to streaming online by following this link: Purchase James Horner Seminar – Artfilms

This article, posted nearly two years ago, is really cool. He looks so young in the photos. Obviously a lot has happened in the past two years. To read this for the first time, for me at least, is interesting to hear about the process of film composing and recording the score to a movie as an intimate private process not seen to the public eyes. Thank you for posting this. Zoe