2 James Horner’s place in film music history

2.1 A Golden Age composer

As we briefly revisit the principal characteristics of the Golden Age sound, it will become apparent to the reader how much of an heir of the Golden Age James Horner really was.

a. Language: James Horner the emotionalist

One: the musical language of the Golden Age is tonal and late-romantic, inspired mainly by Middle Europe’s romantics (Richard Wagner in particular) and the Americana idiom of Aaron Copland. Romantic tonality is preferred because it is best suited to the kind of dream-factory that Hollywood was (and in many ways still is).

Two: Golden Age composers adhered to the richly orchestrated sound of the late-nineteenth-century symphony orchestra. This choice must also be seen in narrative terms: “the symphony orchestra is the richest ensemble as to instrumental timbres and is capable of so many color combinations and hues as to make it completely versatile in meeting a wide array of narrative demands.” (Emilio Audissino, John Williams’s Film Music, p. 37)

Three: Golden Age composers showed no compunction in highlighting the emotional content of a scene and were not afraid to wear their emotions on their sleeves.

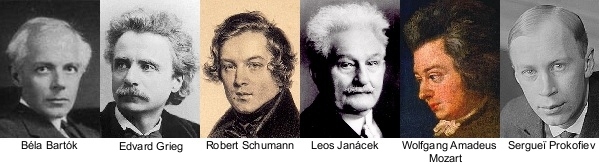

Sometimes the result of budget restraints, sometimes the fruit of a deliberate artistic choice, there is definitely an electronic undercurrent in James Horner’s decades-spanning career, as evidenced by scores such as The Name of The Rose (1986), Where The River Runs Black (1986), Bopha (1993), Southpaw (2015) and The Forgotten (2004). However, by and large, he always had a great penchant for themes and melodies developed in the symphonic, orchestral tradition. In addition to the influences listed above, James Horner had a great love of Russian giants such as Prokofiev and Rachmaninov, and he had a soft spot for the vast legacy of melodies found in (folklore) traditionals, especially the wistful tunes of Ireland. All in all, Horner had a huge amount of colors to draw from.

In keeping with the Golden Age rules but even more overwhelmingly so, James Horner always used to home in on the plight of the protagonist(s). Whether it was the strained relationship between Kirk and Spock in his two Star Trek scores (1982 and 1984 respectively), Tristan Ludlow’s geographic and emotional odyssey in Legends Of The Fall (1995) or the gut-wrenching drama of Kathy Nicolo and Colonel Behrani in The House Of Sand And Fog (2003), rendered in uncharacteristically subdued, wave-like movements, characters always stand front and center in James Horner’s scores.

Very often, Horner focused his attention on female protagonists, supplying them with particularly elegant and meaningful musical material: Rose (Kate Winslet) in Titanic (1997), Elena De la Vega (Catherine Zeta-Jones) in The Mask Of Zorro (1998), Alicia Nash (Jennifer Connely) in A Beautiful Mind (2001) or Tania Chernova (Rachel Weisz) in Enemy At The Gates (2001). In the case of Rebecca (Q’Oriana Kilcher) in The New World (2006), Horner built his entire score around the New-Zealand singer Hayley Westenra, whose vocal work is the perfect embodiment of the movie’s heroine, Pocahontas. True, the story was important, but Horner’s true intent lay elsewhere. In fact, Terrence Malick’s direction was so painstakingly detailed that Horner wanted to mirror this attention to detail with an equally multi-layered portrayal of a young woman’s emotional inner life that audiences could understand and explore to the fullest. However, Malick grew wary of Horner’s focus on the Indian girl and ended up throwing out the entire musical architecture that the composer had created around her. In fact, the FYC album presented to the Academy Members featured alternates of many cues, stripped of Westenra’s voice.

In The Amazing Spider-Man (2012), Horner wanted to go against the prevailing superhero template by composing lots of lengthy intimate and mysterious cues for piano or woodwinds, in order to focus squarely on the story’s characters. When he read the sequel’s script and saw that it was all action and very little character, he decided to leave the franchise.

In persistently composing intimate music that spoke to the characters and their emotions, Horner always subjected action to character development: as early as 1982, he said that the action in Star Trek II (1982) “would take care of itself” and instead decided to focus more on the friendship between Kirk and Spock. In Legends Of The Fall (1994), he scored young Samuel’s death with an action set piece dripping with drama – the musical cue in question is carried even more by the drama than by the (spectacular) action writing. The climactic War cue from Avatar (2009) sees Horner spending at least as much time crying out the losses and celebrating the victories as he does building the tension and pacing the action. If Horner’s action music is so successful, it is not because it is so exhilarating and well-composed (which it definitely is), but because he sees it as an opportunity to mobilize his themes and melodies to even greater dramatic effect. In Horner’s book, character always came first.

Interestingly, James Horner’s music became increasingly tinged with a vague sense of elegant sadness. The Perfect Storm (2000) could have been scored as a straightforward action score, but Horner brought to it a sense of beautiful tristesse, even during the high-octane action set pieces. It is very tempting to see this ever-present melancholy, sober thoughtfulness and pensiveness as a significant quality of James Horner’s personality.

« I always look for colors that are wistful and have a feeling of past and mean something to me. (…) It's very important for the music to be very intimate to me. I can always make it sound big but certain instruments are just key to unlocking the heart, which is what all film music is about. » 1

This pervasive sense of melancholy is a common thread running through Horner’s oeuvre. It was present right at the start of A Few Days In Weasel Creek (1981) before blossoming in Testament (1983) and Cocoon (1985).

In this respect, consider how particularly fond Horner was of Irish music, which is permeated by the same melancholy and which emotionally underpins scores such as Braveheart (1995), The Devil’s Own (1997), Bobby Jones: Stroke Of Genius (2004) and even Titanic (1997).

“Celtic music has its own tonality that I like a lot. This melancholy can also be found in early English and Irish music. Even when the melody is cheerful, the tonality causes the pieces to sound strangely and beautifully sad.” 2

In short, James Horner could be called an emotionalist.

b. The film score as a storytelling device

Golden Age scores play nearly continuously, a steady stream of musical cues which serve as both a constant narrative and an emotional guide for the audience. In doing so, Golden Age music tends to be and even strives to be “inaudible” in that it guides the audience’s attention to story and emotions in a subconscious or, at most, semi-conscious way. In this respect, it is the aural counterpart of continuity editing, whereby “invisible” cuts are designed to lead the audience seamlessly from one shot to the next: matching eye lines, cutting on action etc. Apart from its language (the romantic idiom), Golden Age film music is essentially both a storytelling device and a means to deliberately guide and even manipulate the audience’s emotional response to the visuals.

James Horner was perhaps the ultimate storyteller, because uniquely in the oeuvre of a Hollywood composer, he deliberately attempted to structure movie stories on no fewer than three levels.

There’s the micro-level of the musical cue: Horner loved to compose lengthy cues running well over six minutes. He did this for two reasons. One is the already mentioned “inaudibility” criterion: after a couple of minutes, we the audience stop paying attention to the music, which allows Horner to sneak into our subconscious and go to work. It is the same way continuity editing goes about directing our attention from one shot to the next, providing smooth transitions that do not call attention to themselves. The added advantage of a long musical cue is that Horner could work on its architecture. As you will read in our ongoing series “Standout Set Pieces”, Horner always structured lengthy cues in admirable ways. For one thing, he made sure they had a beginning, a middle and an end. In fact, on the soundtrack album, many of those cues play like self-contained symphony movements, with fully realized cadenzas.

Horner’s keen attention to architecture also occurred on the macro-level of the score. In this respect, his talents were arguably unrivaled in film music history. Here is a composer who not only respects and mirrors the storyline of the story at hand, but also, in parallel, constructs his own story. In Project X (1986), Horner scored Virgil’s first successful flight on the monitor and, resorting to a technique called some sopra, used the same musical progression for the movie’s climax, as the monkey takes a real plane up into the sky. At the moment of take-off, Horner held back in the simulator room but unleashes a triumphant cymbal clash during the story’s finale. The cymbals are meaningful in two respects: they are in keeping with the unabashedly extraverted nature of the Golden Age template, and they are Horner’s way of acknowledging that Virgil’s flying skills are now fully matured and the scene is set for a triumphant conclusion. Horner scored the first and second acts of The House Of Sand And Fog (2003) using only electronic instruments.

As in Field Of Dreams (1989), the orchestrating decision to introduce the orchestra at the start of the third act is both meaningful and incredibly effective from an emotional point of view: the composer and the director had assembled the building blocks in an unassuming, even somewhat understated way, and by the third act, they were able to capitalize on their investment with a succession of devastatingly emotional pay-offs. On a subconscious level, the emotional impact registers even more strongly in the viewer’s perception because of the shift from the electronic to the organic sound palette. In general, Horner realized that the classic Hollywood story is about a flawed protagonist who undergoes a total transformation over the course of three acts, reaching redemption at the end of the story. Like the screenplay writer, who introduces the character elements at the start of the story and uses them to ratchet up the tension and broaden the action, James Horner used his themes and motifs tentatively at first, allowing them to blossom and expand as the story evolves. This means that many Horner scores lend themselves easily to a nicely chronological CD album presentation. Indeed, Horner usually presented the cues in film order, and whether or not a cue was edited or omitted was often only determined by the amount of music that a CD can hold.

Storytelling occurs within individual cues (micro-level) and it defines the arc of the entire score (macro-level). Moreover, uniquely in the history of film music, building stones such as themes and motifs composed for one score may return in a later one, creating intricate and meaningful interrelationships which transform James Horner’s oeuvre into something of a “meta-score”. We will return to this meta-level later on.

c. Academic background

Golden Age composers were all conservatory-bred scholars, who often maintained a career in the concert hall in parallel with their work in Hollywood movies. James Horner fits the profile: after obtaining a PhD in musicology, he started out as a writer of contemporary music for the concert hall. However, Spectral Shimmers (1979) turned out to be a frustrating experience: the piece was performed only once and failed to find an audience. Frustrated by the world of academia, Horner turned to Hollywood and started composing for movies. By the early 2010s, the film music scene had evolved to a point so far removed from the Golden Age template that Horner decided to maintain his relationships within the film business but venture a second foray into the concert hall.

“I haven’t done a lot of, what I call [thinks], ‘serious music’ and ‘serious compositions’ for a long time. That was my whole world until I was about 25, 26 years old and got into film music. Up until then I didn’t know anything about film and I was not interested in film. I tried to do ‘serious music’, to get commissions… that was my whole background. I also studied classical music for many years. And now (ed. note: in 2012), it’s funny, I’m starting to get commissions to write ‘serious pieces’. And I’m actually going to do that a little bit. I really love writing for film though. It gives you the possibility to reach a lot of people with your music that you probably wouldn’t aside from composing for film.” 3

Prior to his untimely death, Horner managed to compose two pieces, Pas De Deux and Collage, which premiered in 2014 and 2015, respectively.

d. Themes and melodies

In line with the “inaudibility” criterion, the Golden Age style uses leitmotivs and themes to identify characters, situations and even ideas, so that the mere appearance of a musical building stone suggests the presence of the character or idea on screen. David Raksin composed the ultimate monothematic score for Laura (1944), in which the excessively used theme enabled him to suggest the constant presence of the dead protagonist in the obsessed minds of the other characters. Golden Age scores employ the techniques of themes and variations, leitmotivs, extensive synchronism (to the point of Mickey-Mousing) and dialogue underscoring (Robin and Marian’s dialogue scenes in Korngold’s The Adventures Of Robin Hood (1938) are a textbook example).

James Horner was a melodist beyond compare, his themes beauties in and of themselves. The seven-minute Saying Goodbye To Those You So Love (A Beautiful Mind, 2001) is one example, but there are a hundred more.

It’s true that James Horner’s themes have not become as popular as John Williams’s or Ennio Morricone’s, partly due to the popularity of the movies for which they were composed. This is another instance of how intimately the fate of a score is linked to its movie. History will remember Rose’s theme thanks in part to the worldwide hit My Heart Will Go On performed by Celine Dion for the end title of Titanic (1997). Who knows: had Horner composed the music for the Harry Potter saga – he was director Chris Columbus’s first choice – he might very well have come up with a theme as memorable as John Williams’s. That said, James Horner never consciously chased after the memorable theme.

“I am not especially a composer of themes, especially since themes are not what matters most in my music. A flower without earth will not bloom, a stained-glass window could not exist without its cathedral. Likewise, a theme without any kind of harmonic architecture means very little to me. (…) The theme is always at the service of the phrase, not the other way around.”4

It would be prejudiced and short-sighted to assess James Horner’s music on the sole merit of its musical building stones. Themes and melodies have an immediate impact and often determine a score’s accessibility, but they are just one part of the scoring process, a stone in the cathedral among such other stones as harmony, rhythm, timbre, tempo, instrumentation, orchestration… James Horner thought of a score as an organic whole rather than a collection of individual themes or melodies. His greatest merit would have to be the artistic process seen in its entirety: emotions, colors, storytelling, meaningful musical quotes, harmony and silence.

2.2 The art of quoting

A music scholar, James Horner was astutely aware of the vast tradition of music outside Hollywood. While all film composers consciously or subconsciously quote the classics, Horner did it more deliberately and more extensively than anyone else. “I am a musicologist, a doctor of music. Therefore I listened to, studied and analyzed a lot of music. I also enjoy metaphors, the art of quoting and of cycles.”

There are two reasons why a film composer would use a quote. The director or producer might ask for music that closely resembles the temp track (existing music temporarily tracked into a scene to give the composer an idea of what the filmmakers want). Exactly how much the resulting cue will sound like the temporary music depends on the leeway given to the composer and on his ability to distance himself from the source and still meet the filmmakers’ demands. When scoring Ant  Rodeo (Honey I Shrunk The Kids, 1989), James Horner was asked to mimic Dave Grusin’s Fratelli’s Chase from The Goonies (1985). Film composers usually do not like temp tracks: while they allow for easier communication between musically trained and musically untrained artists, directors often fall in love with the temp track’s melodies rather than with their general emotional tone, in effect forcing the composer down the tricky path of thinly-veiled plagiarism. Most of James Horner’s quotes were a different matter altogether, the composer himself opting for a quote, often from the classical repertoire, because it comments intelligently on the visuals or the story, or because it adds a symbolic or emotional dimension to the scene. For example, Horner took the melody of Mar Stanke-Le, an obscure Bulgarian harvest song, and turned it into the fabulous theme for Elora Danan in Willow (1988). The lyrics of Mar Stanke-Le suggest a motherly love that transcends death, mirroring the fate of the infant girl who becomes an orphan after her mother is ruthlessly executed.

Rodeo (Honey I Shrunk The Kids, 1989), James Horner was asked to mimic Dave Grusin’s Fratelli’s Chase from The Goonies (1985). Film composers usually do not like temp tracks: while they allow for easier communication between musically trained and musically untrained artists, directors often fall in love with the temp track’s melodies rather than with their general emotional tone, in effect forcing the composer down the tricky path of thinly-veiled plagiarism. Most of James Horner’s quotes were a different matter altogether, the composer himself opting for a quote, often from the classical repertoire, because it comments intelligently on the visuals or the story, or because it adds a symbolic or emotional dimension to the scene. For example, Horner took the melody of Mar Stanke-Le, an obscure Bulgarian harvest song, and turned it into the fabulous theme for Elora Danan in Willow (1988). The lyrics of Mar Stanke-Le suggest a motherly love that transcends death, mirroring the fate of the infant girl who becomes an orphan after her mother is ruthlessly executed.

Rodeo (Honey I Shrunk The Kids, 1989), James Horner was asked to mimic Dave Grusin’s Fratelli’s Chase from The Goonies (1985). Film composers usually do not like temp tracks: while they allow for easier communication between musically trained and musically untrained artists, directors often fall in love with the temp track’s melodies rather than with their general emotional tone, in effect forcing the composer down the tricky path of thinly-veiled plagiarism. Most of James Horner’s quotes were a different matter altogether, the composer himself opting for a quote, often from the classical repertoire, because it comments intelligently on the visuals or the story, or because it adds a symbolic or emotional dimension to the scene. For example, Horner took the melody of Mar Stanke-Le, an obscure Bulgarian harvest song, and turned it into the fabulous theme for Elora Danan in Willow (1988). The lyrics of Mar Stanke-Le suggest a motherly love that transcends death, mirroring the fate of the infant girl who becomes an orphan after her mother is ruthlessly executed.

Rodeo (Honey I Shrunk The Kids, 1989), James Horner was asked to mimic Dave Grusin’s Fratelli’s Chase from The Goonies (1985). Film composers usually do not like temp tracks: while they allow for easier communication between musically trained and musically untrained artists, directors often fall in love with the temp track’s melodies rather than with their general emotional tone, in effect forcing the composer down the tricky path of thinly-veiled plagiarism. Most of James Horner’s quotes were a different matter altogether, the composer himself opting for a quote, often from the classical repertoire, because it comments intelligently on the visuals or the story, or because it adds a symbolic or emotional dimension to the scene. For example, Horner took the melody of Mar Stanke-Le, an obscure Bulgarian harvest song, and turned it into the fabulous theme for Elora Danan in Willow (1988). The lyrics of Mar Stanke-Le suggest a motherly love that transcends death, mirroring the fate of the infant girl who becomes an orphan after her mother is ruthlessly executed.

Horner (in)famously used and revisited the eerie strings of Gayaneh’s adagio by Aram Khachaturian as a metaphor for the machinations of the military industrial complex, either implicitly, in 1986’s Aliens (where it also commented on the emptiness of space), or explicitly, in Electronic Battlefield from Patriot Games (1992) and the largely unused Navajo Dawn from Windtalkers (2002).

“I studied music for so long, so many years… Prokofiev, Benjamin Britten, Mahler are as close to me as anything. Further on I love medieval, early renaissance and Irish music. All those people and styles influenced me and my writing. I cannot and don’t want to completely remove myself from that.” 3

Here’s an incomplete list of music James Horner quoted during the first part of his career:

- Sergei Prokofiev – The Death of Tybalt (Romeo & Juliet – 1935)

- in Stealing the Enterprise (Star Trek II – 1982), Escape from the Tavern (Willow – 1988)

- Benjamin Britten – Peter Grimes (1946) in The Forest (The Journey of Natty Gann, 1986) and the Main Title of An American Tail (1986)

- Sergei Prokofiev – Violin Concerto No. 1 (1916-1917) in An American Tail (1986).

- Alexander Borodin – In The Steppes of Central Asia (1880) in An American Tail (1986).

- Alexander Mosolov – Op.19 The Iron Foundry in Aliens (1986)

- Krzysztof Penderecki – The Dream Of Jacob (1976) in Aliens (1986)

- Béla Bartòk – The Wooden Prince (1914-1916) in The Great Migration (The Land Before Time, 1988).

- Aaron Copland – Hoe-Down (Rodeo – 1942) in In Training (An American Tail: Fievel Goest West, 1991) and Ant Rodeo (Honey I Shrunk the Kids, 1988)

- Raymond Scott – Powerhouse (1937) and Nino Rota – Amarcord (1973) in Honey I Shrunk the Kids (1988)

- Aaron Copland – Our Town (1940) in Field of Dreams (1989)

- Vaughn Williams – Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis in Burning the Town of Darien (Glory, 1989) and Troy (2004).

- Sergei Prokofiev – Battle on the Ice (Alexander Nevsky, 1938) in many scores.

- Leos Janacek – Glagolitic Mass (1926) in Willow (1988)

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Confutatis (Requiem, 1791) in Willow (1988)

- Béla Bartòk – Cantata Profana (The Nine Splendid Stags, 1930) in Willow (1988)

- Robert Schumman – Symphony Nº 3 "Renish" in Willow (1988)

- Sergei Prokofiev – Cantate for the 20th anniversary of the October Revolution in Willow (1988), Red Heat (1988) and in The Land Before Time (1988).

- Edvard Grieg – Arabian Dance (Peer Gynt, 1874) in Journey Begins (Willow – 1988) and The Journey Begins (Once Upon A Forest, 1993)

This list is just the tip of the iceberg, showing how cultured James Horner was as a musician. He liked to draw on Czech, Bulgarian, Norwegian, Russian, German, Hungarian and American influences and saw his own oeuvre as a modest cog in the wheels of the vast history of music.

Every artistic creation stands on the shoulders of what came before. Likewise, every quote has its own meaning and is in no way intended to be a diluted version of the source material. Rather, quotes keep the repertoire alive, perpetuating a tradition which has existed for 500 years.

“I have my own definition of my music, and every new score is a new step in that story of musical expression. So yes, my music contains “my” definition of music, what I bring to it myself, but also codas in the style of Bruckner, techniques used by Stravinsky and Debussy etc., and within this vast repertoire I build my own repertoire.” 4

For many more examples of James Horner’s art of quoting, please turn to Jean-Baptiste Martin’s “It’s Logical”, an ongoing series of articles on the subject that can also be found on this website. We recommend two articles in particular: Willow Between Quotes and Between Intelligence and Sensitivity: Two Dissected Untruths.

2.3 The oeuvre as a constantly evolving patchwork of colors

“This may sound like something of a paradox, but looking at the past is a constant source of moving forward instead of backward. I often use existing music to create new music, and for me, looking back is a way of looking far ahead. The movies I work on allow me to remodel and repurpose colors I live with every day.” 5

James Horner viewed his own oeuvre as a constantly evolving patchwork of colors. He often likened his composing style to painting and had no compunction about re-using even his own themes or motifs from one score to the next. Sometimes, it was a matter of simple sensibility: a theme or color that works fine here might also work there, and the net effect would only become visible when you looked at a theme as part of the artist’s total oeuvre.

“There’s no end to how far you can take this element of continuity, and I would use references until I run out of inspiration. The world of sounds is limitless and no one has ever used all of it.” 4

Some of the re-use was seemingly arbitrary: Horner reprised one of the main themes from The Four Feathers (2001) almost note for note in For Greater Glory (2012) for no other reason than that the melody had more to speak to than just the monumental aspects of the 2001 movie; it had the potential to become a beautiful love theme in the 2012 film. Very often, though, the re-use of themes was downright intentional. Horner took his exuberant Star Trek / Rocketeer ending and had fun with it at the end of The Legend Of Zorro (2005) before expanding upon it in the Flight (Demonstration Music) cue from The Fourth Horseman (2010). He expanded the ape motif from Project X (1986) into an expansive main theme for another ape, Mighty Joe Young (1998). Casper’s melancholy theme (composed in 1995) returns prominently in the final minutes of The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008) and rightly so: Casper the friendly ghost has one last dance with Christina Ricci before becoming a boy, which finally opens the way for both characters to have a real-life relationship. Essentially, this scene is a mirror of Arthur and Lucinda Spiderwick’s moving reunion, the story’s two lovers finally united after spending decades alone and sailing off into some sort of magic life across the boundaries of time. The journey from a magical realm to reality (Casper) and the one from reality to a magical realm (Spiderwick) is thoughtfully and poignantly rendered by Horner with the same melody.

This patchwork-approach was arguably prompted, at least in part, by the realization that the same kind of scenes returned with every new project. How many reunion scenes, chase scenes, superhero-going-to-town scenes, all-is-lost scenes etc. can one score without entertaining the idea of tying them together in one way or another? However, the conscious, intellectual and single-minded way in which Horner went about this endeavor sets him apart from his peers.

“There’s always going to be criticism and second-guessing, but it has not bothered me. My job is not to please, it’s to express myself. Which I do.” 4

Of course, the casual listener cannot realistically be expected to have this kind of intimate knowledge of one artist’s oeuvre. This has resulted in Horner being attacked (sometimes savagely) for (self-)plagiarism and an unwillingness to reinvent himself.

“Reinvention is a term that doesn’t mean anything to me in the classical language. You reinvent yourself in jingles, in easy-listening, but not in film music as I understand it. As far as I am concerned, continuity is not necessarily about reinvention, quite the contrary!” 4

2.4 Versatility and experimentation

“I like to combine elements from very different schools – serial music, impressionism, the dodecaphonic tradition, purely classical music, baroque – and turn them into something that defines me and which I take pride in. Something that defines a composer.” 4

It would be a disservice to Horner’s vast talents to see the artist only as an heir of the Golden Age style. In fact, Horner often deviated from the mold to create wildly experimental scores, displaying an astonishing versatility. Much more so than his Golden Age counterparts, James Horner liked to venture into undiscovered countries, frequently adding ethnic, vocal and electronic elements to the orchestral palette. The Four Feathers (2001), Beyond Borders (2003), Apocalypto (2006) and Avatar (2009) are among the finest examples of this diverse palette of sounds.

This fascination with the human voice, electronic sounds and ethnic instruments has always been one of Horner’s strong suits, leading to extensive improvisation and experimentation.

“I have always been on the cutting edge of the textures, be they electronic, be they weird instruments from wherever, ethnic instruments… I started using electronics a lot; maybe because I was doing more of improvisatory scores–you would never know that they were improvised because there were no notes. I would do the scene and I would just play it piece by piece into the film until the scene is completed and there were no notes. When I first started doing it, no one had done that before.” 1

James Horner’s first experiments with electronic music led to 48 HRS (1982), Gorky Park (1984) and Commando (1985). He took the next step with The Name Of The Rose (1986).

Recorded in Munich, Germany, the end product mixes together music instrumentation both ancient and modern with a side of synthesizers and other instruments reminiscent of the Middle Ages: chimes, bells, a lute, a zither, a harp.

“The idea was to have perfect sound samples, digitally, of medieval instruments, so that I could play those instruments by myself. And it worked out really quite well… it was a long time ago and we worked with very early types of synthesizer programs. There I got in contact with Hans Zimmer, who back then was the representative of Fairlight, a producer of synthesizers. He delivered us new parts almost every day. We had sampling sessions for about two weeks. Players from all over Germany and Europe played wired medieval instruments.” 6

Director Jean-Jacques Annaud insisted on an experimental score:

“We were the first ones to use samples. We were using medieval instruments and they could not realistically play together. For the first time in the history of film music, we had two semitrailers full of instruments brought in from Australia. Today, all you would need is a smartphone! We went to museums looking for early musical instruments and then recorded their notes – Hans Zimmer recently reminded me that this can now easily be done with a computer.” 7

During The Name Of the Rose promo tour, Baden-Baden’s Südwest radio produced a short documentary on James Horner for German television. The composer is seen seated in his studio stuffed with records and a vast array of synthesizers which he called “the Giorgio Moroder corner”, referring to the famous Italian composer and arranger of electronic music. It serves as further proof of Horner’s fascination with electronic music.

Field Of Dreams (1989) is another fine example of improvisation. Horner walked into the recording sessions studios with only themes in his head and a couple of musician friends on the recording stage: pianist Ralph Grierson, synthesizer specialist Ian Underwood and French horn player James Thatcher. As the improvisation progressed, Horner called in Tony Hinnigan and Mike Taylor, the two flutists who performed on Willow (1988). Director Phil Alden Robinson stated at the time that James Horner “was going through an incredibly creative phase. He had no written score whatsoever and the themes came pouring out of his fingers in an almost magical way.” (Phil Alden Robinson, Jusqu'au bout du rêve by Steve Olson, Dreams magazine 2001) Bar by bar, the musicians built up the cues based on the timings of a locked movie cut. The “improvisation” was based on the themes that Horner had in his head, and two-thirds of the score were never written down. In the end, they had to hire a copyist to get a transcription which was handed over to ASCAP, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers.

James Horner liked to transform the ethnic instruments into dramatic and storytelling elements: the Japanese shakuhachi, Jamaican percussion, Eastern European cimbalom… The instruments’ original ethnic quality became a specific color that helped shape the audience’s subconscious response to the images and the sound effects. From a dramatic point of view, the instrumental color was there to emphasize the tone of the scene, go against it or impact the material in yet other ways. In doing so, James Horner tried to break away from the obvious genre clichés and provide himself with a base for experimentation in the vein of illustrious predecessors like Bernard Herrmann and Ennio Morricone.

Horner also used counterpoint as a way of creating unusual sound worlds, like the bass lines in Uncommon Valor (1983). The obstinate repetition (1-2/1-2/1-2/1-2) is pitted against the military drumroll motif, the searing shakuhachi (representing Vietnam), the oriental instruments and the cimbalom runs. All these sounds play alongside well-known elements, such as brass accents, dissonant trumpets and string embellishment, everything coalescing into a dense sound world that successfully conveys urgency, danger and patriotic fervor. The combination of instruments from wildly different worlds is always interesting and reflects the composer’s ambition to translate the movie’s visual universe into a musical one. Some musical recipes harken back to romantic or contemporary templates, others defy classification. The unique architecture of Horner’s score for The Four Feathers (2002) is an excellent example of this deliberate fusion approach:

“On the one hand, there’s the western influence and my typical colors. On the other hand, there’s a more ethnically flavored aspect, vaguely linked to the locale, and holding these two elements together was the incredibly pure voice of Rahat Nusrat Fateh Khan.” “The music goes from very simple movements with themes and motifs to harmonies which are sometimes conventional, sometimes modal, attuned to the vocal work by Rahat Nusrat Fateh Khan (…) I played around with the notions of fusion, opposition and contrast in an effort to have the vocal element take center stage and, I hope, produce something refreshingly unusual in film music.” 8

During the last period of Horner’s career, at the height of the Digital Age, Avatar (2009), The Karate Kid (2010) and The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) provide an elegant mix of electronic, orchestral and vocal elements. All three movies feature fun and contemporary-sounding scores consisting of various (and varying) musical elements, showing James Horner once more as a master of his craft, both as a musician and as a dramatist.

2.5 The musical potential of silence

“I like to tie a score together beyond its individual parts, and I do not care for end title cues that end up going nowhere.” 9

Long after nearly everyone else had stopped composing self-contained end title cues, James Horner considered the end credit crawl as an opportunity to present final statements of the score’s often numerous themes. A common thread running through those often elaborate end title cues is the way they end: in a mixture of meditation and utter silence. James Horner is in fact something of a mystic, the Greek word “myein” meaning “to close the eyes”.

In the end title cue from The Devil’s Own (1997), Horner leaves the listener wondering if the bodhrán drums will ever cease. At this point, the bodhráns are actually the music’s last orphaned sounds, all that’s left of the cue now that silence is taking over. Is silence more meaningful than music? What remains of instruments and their sounds once they are dropped into an ocean of silence? Is silence as musical as music, or perhaps even more? James Horner as an artist seemed to seek out the  musical potential of silence. In this composer’s case, the notion of mysticism is to be understood in a strictly non-religious sense. Again, it is tempting to see this mysticism as a window to the artist’s soul. Right from the start of his career, Horner opted to start the end title cue with luxuriously orchestrated statements of theme and work his way down to a solo instrument and / or a fade-out into utter silence. Consider the similarly constructed end titles to An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). Consider An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), a single violin note carrying the unused end title’s entire final minute; the pensive fading of drums capping off Glory (1989); the magic motif engaging in a sort of perpetuum mobile at the end of Willow (1989); another and surprisingly lengthy perpetuum mobile finishing The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008); and finally the (often three) cadenzas separated by silences that Horner would use in score after score after score, The Land Before Time (1988) and Searching For Bobby Fischer (1993) just two of many examples. Combine this with instances like the highly musical pauses built into the mammoth opening cue of Enemy At The Gates (2001) and an unmistakable pattern starts to form: James Horner the Mystic saw silence as an integral part of music, sometimes to surprising

musical potential of silence. In this composer’s case, the notion of mysticism is to be understood in a strictly non-religious sense. Again, it is tempting to see this mysticism as a window to the artist’s soul. Right from the start of his career, Horner opted to start the end title cue with luxuriously orchestrated statements of theme and work his way down to a solo instrument and / or a fade-out into utter silence. Consider the similarly constructed end titles to An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). Consider An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), a single violin note carrying the unused end title’s entire final minute; the pensive fading of drums capping off Glory (1989); the magic motif engaging in a sort of perpetuum mobile at the end of Willow (1989); another and surprisingly lengthy perpetuum mobile finishing The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008); and finally the (often three) cadenzas separated by silences that Horner would use in score after score after score, The Land Before Time (1988) and Searching For Bobby Fischer (1993) just two of many examples. Combine this with instances like the highly musical pauses built into the mammoth opening cue of Enemy At The Gates (2001) and an unmistakable pattern starts to form: James Horner the Mystic saw silence as an integral part of music, sometimes to surprising  effect. At one point during the 2013 Vienna concert (given in the composer’s honor and conducted by David Newman), the audience started a round of applause before the Titanic Suite had reached its last note, not realizing that the silence between the penultimate and the ultimate note was intentionally written into the music. On the Blu-ray edition of the concert, James Horner is seen smiling as he watches conductor David Newman trying to hold off the applause.

effect. At one point during the 2013 Vienna concert (given in the composer’s honor and conducted by David Newman), the audience started a round of applause before the Titanic Suite had reached its last note, not realizing that the silence between the penultimate and the ultimate note was intentionally written into the music. On the Blu-ray edition of the concert, James Horner is seen smiling as he watches conductor David Newman trying to hold off the applause.

musical potential of silence. In this composer’s case, the notion of mysticism is to be understood in a strictly non-religious sense. Again, it is tempting to see this mysticism as a window to the artist’s soul. Right from the start of his career, Horner opted to start the end title cue with luxuriously orchestrated statements of theme and work his way down to a solo instrument and / or a fade-out into utter silence. Consider the similarly constructed end titles to An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). Consider An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), a single violin note carrying the unused end title’s entire final minute; the pensive fading of drums capping off Glory (1989); the magic motif engaging in a sort of perpetuum mobile at the end of Willow (1989); another and surprisingly lengthy perpetuum mobile finishing The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008); and finally the (often three) cadenzas separated by silences that Horner would use in score after score after score, The Land Before Time (1988) and Searching For Bobby Fischer (1993) just two of many examples. Combine this with instances like the highly musical pauses built into the mammoth opening cue of Enemy At The Gates (2001) and an unmistakable pattern starts to form: James Horner the Mystic saw silence as an integral part of music, sometimes to surprising

musical potential of silence. In this composer’s case, the notion of mysticism is to be understood in a strictly non-religious sense. Again, it is tempting to see this mysticism as a window to the artist’s soul. Right from the start of his career, Horner opted to start the end title cue with luxuriously orchestrated statements of theme and work his way down to a solo instrument and / or a fade-out into utter silence. Consider the similarly constructed end titles to An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). Consider An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991), a single violin note carrying the unused end title’s entire final minute; the pensive fading of drums capping off Glory (1989); the magic motif engaging in a sort of perpetuum mobile at the end of Willow (1989); another and surprisingly lengthy perpetuum mobile finishing The Spiderwick Chronicles (2008); and finally the (often three) cadenzas separated by silences that Horner would use in score after score after score, The Land Before Time (1988) and Searching For Bobby Fischer (1993) just two of many examples. Combine this with instances like the highly musical pauses built into the mammoth opening cue of Enemy At The Gates (2001) and an unmistakable pattern starts to form: James Horner the Mystic saw silence as an integral part of music, sometimes to surprising  effect. At one point during the 2013 Vienna concert (given in the composer’s honor and conducted by David Newman), the audience started a round of applause before the Titanic Suite had reached its last note, not realizing that the silence between the penultimate and the ultimate note was intentionally written into the music. On the Blu-ray edition of the concert, James Horner is seen smiling as he watches conductor David Newman trying to hold off the applause.

effect. At one point during the 2013 Vienna concert (given in the composer’s honor and conducted by David Newman), the audience started a round of applause before the Titanic Suite had reached its last note, not realizing that the silence between the penultimate and the ultimate note was intentionally written into the music. On the Blu-ray edition of the concert, James Horner is seen smiling as he watches conductor David Newman trying to hold off the applause.

This fascination with silence fits accounts of the composer as an introverted, somewhat shy human being, an artist using his own fragility as a jumping-off point for a unique musical oeuvre of infinite emotional refinement.

We’re fairly sure that’s how James Horner would want to be remembered.

Article by Kjell Neckebroeck and Jean-Baptiste Martin

Special thanks to David Hocquet, John Andrews, Nick Martin.

Banner by Javier Burgos

Sources:

2 – Interview with James Horner by Didier Leprêtre, Dreams to Dream … 's 1998.

3 – Cinema Musica: Interview with James Horner – Published in Cinema Musica in April 2012 – in German

4 – J.H. Et Des Poussières: James Horner Retrouve La Trace Des Disparues. By Didier Leprêtre and Jean-Christophe Arlon, Cinéfonia (2003), translated back into English by Kjell Neckebroeck

5 – J.H. Et Des Poussières: Mémoire Effacée Et Testament Retrouvé. By Didier Leprêtre and Jean-Christophe Arlon, Cinéfonia (2005), translated back into English by Kjell Neckebroeck

7 – Interview with Jean-Jacques Annaud on Wolf Totem (2015), James Horner Film Music 2015, translated into English by Kjell Neckebroeck

8 – James Horner Ou La Fusion Des Quatres Plumes Dreams Magazine, 2002, by Jean-Christophe Arlon, translated back into English by Kjell Neckebroeck

9 – James Horner, La Légende de Zorro: Le Renard Puissance 10! Cinefonia Magazine by Jean-Christophe Arlon and Didier Leprêtre 2005, translated back into English by Kjell Neckebroeck

Pages: 1 2

Wow…this piece today is going to keep me busy reading for a while. Thank you so much to all concerned. And also for your great piece on Enemy at the Gates. James certainly deserves a place in Film Music history, for all his wonderful pieces, a tribute concert would surely be well placed, bearing in mind it is getting near to his second Anniversary. London is lucky to shortly have the 20years showing of Titanic at the Royal Albert Hall, with concert orchestra. A tribute in itself to the wonderful evening of 27th April, 2015. I really appreciate all your hard work JHFM. Pamela.

JHFM fans based in the UK and Ireland would have had a chance on Friday 22nd February 2019 to watch the documentary ‘Score: Cinema’s Greatest Soundtracks’ broadcast on BBC Four. The documentary can also be viewed for a limited time on the BBC website (www.bbc.co.uk/programmes). Despite its title, the film does not present a ‘top twenty’-style selection of the best known movie scores, but attempts to relate the story and role of music at the cinema from the earliest times back in the era of ‘silent’ pictures, when an intrepid musician on piano or possibly the organ would attempt to keep pace with and interpret the on-screen action for the benefit of the viewers, all the way to the sophisticated kaleidoscope of sounds presented to today’s cinemagoer. For a film lasting just 90 minutes this was a very ambitious undertaking, to say the least.

In truth, fascinating an exercise though it is, ‘Score’ packs far too much into too small a space. It is a veritable ‘who’s who’ of the film composing world, but many of the contributors to the programme, who are among the elite of those active in the profession today, are limited to appearances that last only a matter of seconds. In trying to leave nothing and no one out, the makers have rather ended up skimming across the surface of the subject, rather than exploring the art of composing for film in greater depth, which would have been altogether more informative and satisfying. But having said that, I don’t recall there ever being anything on television before that looked seriously at film music, and as an introduction to this world it has an awful lot going for it, and the finished product was the result of a huge effort by all concerned.

It would have been great if the production team had taken a leaf from the above outstanding overview of film music history and perhaps decided to put together a TV series rather than a one-off special, each episode devoted to one of the four ‘ages’ identified by Kjell and Jean-Baptiste in their highly knowledgeable analysis: the Golden Age, The Silver Age, The Bronze Age and the Digital Age. A quartet of programmes along those lines would allow the many talented practitioners, who make ‘blink and you’ll miss it’ appearances on ‘Score’ and who clearly have a lot more to tell us about what they do, to enlighten viewers in a more compelling way on the joy and beauty of the often underrated and misunderstood art of composing for the big screen. Having said that, someone may be inspired by ‘Score’, which in many ways is a revelation, to take things further, perhaps by producing a series of television profiles that takes in each case a detailed look at the career output of a celebrated film composer.

The question remains of course–what does ‘Score: Cinema’s Greatest Soundtracks’ tell us about James Horner’s place in film music history? Well, one of the frustrations of watching the programme unfold was knowing that JH himself is no longer around to give his considered opinion on the intricacies and mysteries of setting music to film. As one of the film music’s most gifted exponents he had much to say on this field of endeavour in his lifetime and would have made a great impact on ‘Score’ were he still with us.

Nevertheless, the programme was peppered with brief clips of none other than James Cameron, carefully positioned in front of an imposing model of the ‘Titanic’. In light of this visual clue, one rather had the feeling that the makers of ‘Score’ had no intention of letting the film conclude without giving the Maestro credit for his distinguished record of achievement in movie scoring. And this turned out to be the case, for James Cameron, in paying tribute to his friend, ensures that the last word belongs to James Horner.

The final segment of ‘Score’ is captioned ‘Remembering James Horner’. Over the famous scene from ‘Titanic’ of the hero Jack, a study in concentration, drawing Rose, in reclining pose and wearing nothing but the heart of the ocean, Cameron describes how in post-production on the film he received a disc from JH marked ‘sketch’. The piece of music on it was a piano demo of the film’s love theme, which as we all know, turned out to be the greatest ever written for a motion picture. Cameron assumed from the title ‘sketch’ that JH intended the piece to be used for the scene where Jack produces the drawing that Rose had asked him for and duly added it to that point on the soundtrack. However, to JH himself the ‘sketch’ was simply a rough cut of the theme, and was not written with that scene in mind. But Cameron was convinced that the piano solo was perfect, and of course that’s where it stayed, to be rechristened ‘The Portrait’ and released on the ‘Back to Titanic’ cd. Of course, one wonders whether this anecdote is really true, but it’s a great story all the same.

It is of course fitting, wonderful and very moving that the makers of ‘Score’ should pay tribute to James Horner in this way. But by ending on the drawing scene from ‘Titanic’ a very important point is made, not only about James Horner’s place in film music history–a preeminent one for sure–but also about the craft of film scoring in general. ‘Score’ illustrates not only the increasing complexities of the art form as it exists today, with the traditional orchestral approach now augmented by an array of digital and technological tools, but it demonstrates that screen composers are obsessed with novelty, with discovering new instruments and devices that have the potential to give their work something that no one has heard before. For ‘Titanic’ James Horner masterminded, with incredible success, a new way of scoring a period drama, delivering a multifaceted, skilfully layered and richly textured work that served the film perfectly while at the same time was utterly memorable. But in the middle of the score, for the drawing scene, the viewer is treated to nothing more than solo piano. The effect is hypnotic and spell-binding. As the narrative of ‘Score’ reveals, the solo piano is where film scoring began, way back in the days of silent movies. James Horner was of course fully aware of this fact, but also mindful that, no matter how grand and ambitious a film score could become, there is always a place for the simple touch, for going back to how film music was created in the beginning, relying on nothing more than the piano to capture, in a way that no audience could ever forget, the essence of a moment on screen. This, to my mind, is pure genius.